Klee in America

The Phillips Collection showcases the artist’s lasting influence

By Elsa Smithgall, Curator, The Phillips Collection

Paul Klee, Young Moe, 1938. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

“Let each man go where his

heartbeat leads him.”

Paul Klee’s words embody much about the man whose independent spirit and artistic expressions left an indelible mark on the history of modern art in America. The history of art, like the history of ideas, is built on a history of influence. Invention breeds invention; artists are constantly nurturing their imaginations both through contact with the past and through discoveries of their own time.

In accounts of mid-twentieth century American art, Klee’s significance has yet to be sufficiently examined and remains understudied in comparison with such towering figures as Picasso, Matisse, and Kandinsky. The exhibition Ten Americans: After Paul Klee at the Phillips Collection was born out of the desire to probe beneath the surface of the limited scholarship on Klee’s impact on American postwar art and plow a deeper field of understanding into the artistic exchanges that brought Klee’s art, methods, and writings across the Atlantic. In the course of conducting research for the exhibition, my co-curator, Fabienne Egglehöfer, chief curator, Zentrum Paul Klee, and I sought to uncover the paths through which American artists were most likely introduced to Klee’s art and ideology. Central to our undertaking was an understanding that Klee’s importance to American art went beyond admiration or a desire to emulate or copy his style. Drawing on Klee’s inspiring example, each artist assimilated aspects of the Swiss-born artists’ creative practice to develop their own unique forms of expression.

What our research revealed is true of the nature of invention across all disciplines: Influence takes many forms, travels far and wide, and is stirred by contact with others—mentors, teachers, friends, and colleagues. Yet novel art forms and ideas, such as those of Klee, often take time to be absorbed and embraced; indeed many initially are met with skepticism, if not rejection. Enthusiasm for Klee’s work among American audiences did not come overnight. When MoMA organized a solo show for Klee in 1930, the first devoted to a living European artist, the exhibition “enraged visitors,” as reported by MoMA’s director, Alfred Barr.[1] By 1950, however, on the occasion of the largest public display of Klee’s work in the United States, his reputation had risen to such an extent, observed MoMA curator James Thrall Soby, that “perhaps only Picasso among modern painters has rivaled Klee. [. . .] Klee’s art seems as rich in plastic discovery as Picasso’s. He worked as a virtuoso, but with the conscience of a master and a philosopher’s exaltations. Perhaps this is why Klee’s paintings and drawings are more and more influential among younger artists. His influence is rising now even in Paris. [. . .] In America, on the contrary, Klee has for some time been appreciated by artists and laymen, though never in such measure as now.”[2]

In the 1970s, scholar Richard Kagan brought renewed attention to the subject in a two-part article published in Arts Magazine, “Paul Klee’s Influence on American Painting,” one of the first efforts by an American scholar to define more closely the precise nature and extent of Klee’s influence on specific artists. More strides in this direction were made in 1987 in Carolyn Lanchner’s essay “Klee in America,” one of several that figured in the catalogue that accompanied MoMA’s landmark show Paul Klee. In 2006, the first exhibition exclusively devoted to the subject of Klee and America (and one that was presented at The Phillips Collection) laid important groundwork for Ten Americans: After Paul Klee. However, unlike Klee and America, which told the story strictly through the art and life of Klee, Ten Americans is the first museum exhibition to present his work in dialogue with American art.

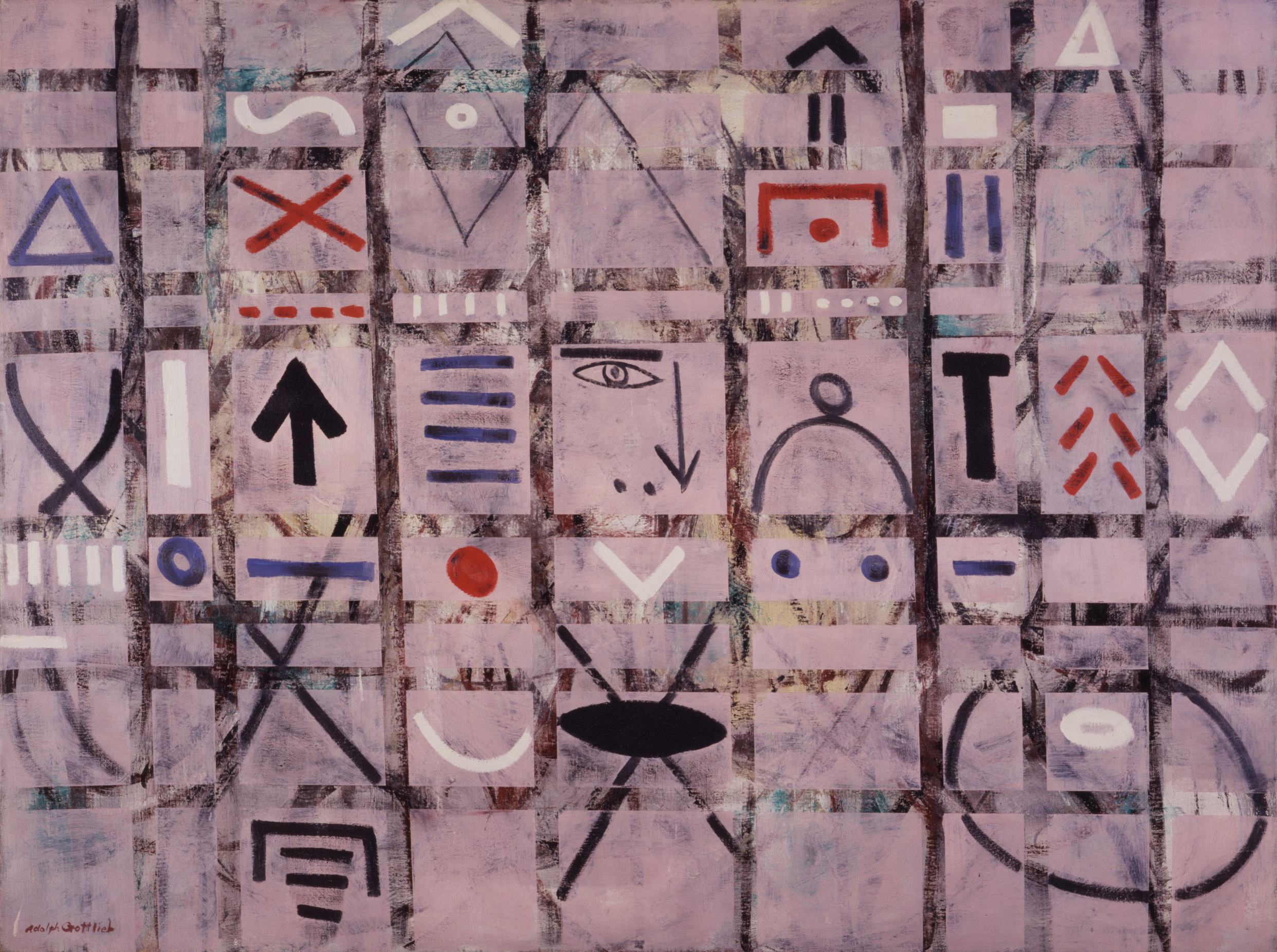

Adolph Gottlieb, Labyrinth #1, 1950, courtesy of Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, New York

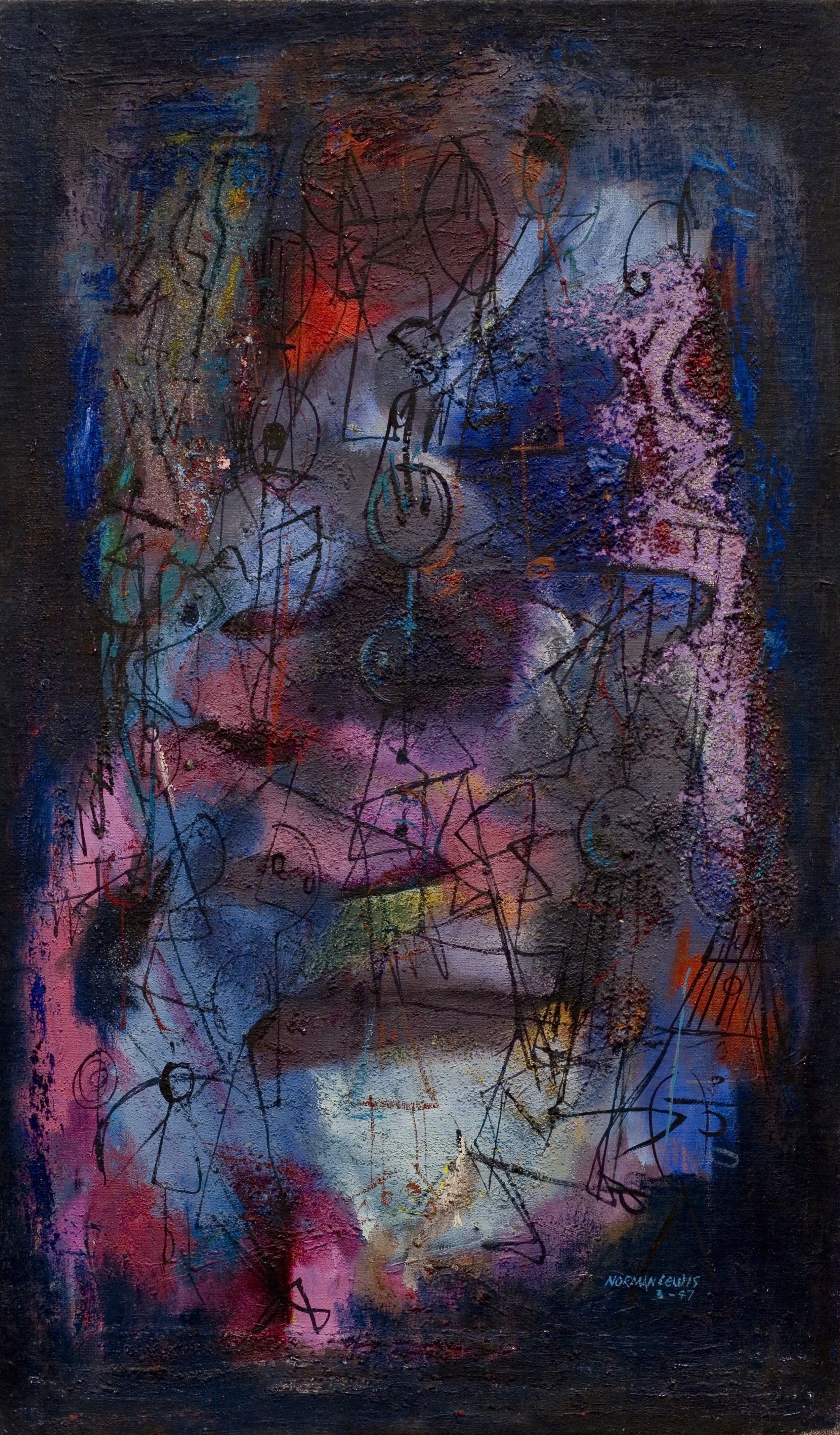

What did such diverse artists as Gene Davis, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, Norman Lewis, Kenneth Noland, Jackson Pollock, Theodoros Stamos, Mark Tobey, and Bradley Walker Tomlin find appealing about Klee? While Klee forged bonds with his American brothers over a number of artistic ideals—from the power of symbolic language and the expressive potential of automatic writing to the vitality of nature’s unseen forces—an essential ingredient of Klee’s significance lies beyond the limits of any single idea, method, or formal solution. Rather, it rests more broadly on the lessons conveyed through Klee’s stylistically open-ended approach that showed the expressive possibilities of synthesizing line and color, figuration and abstraction, and spontaneity and control. These guiding principles continue to strike a chord in our twenty-first century global art world and are a testament to an influencer who is still beloved to this day.

Klee’s significance has and continues to reach beyond the visual arts across disciplines, from the performing to the literary arts. Phillips Collection founder Duncan Phillips was among those who recognized the profound poetic sensibility in Klee’s art, likening his work to that of the English poet William Blake. Today, contemporary poet Lillian-Yvonne Bertram pays homage to Klee in beautifully weaving together her meditations and memories with Klee’s writings in “Klee in Wartime,” the subject of which coincidentally is the focus of a special exhibition now on view at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland.

To journey through Ten Americans: After Paul Klee is to consider how cross-cultural exchanges have fueled and continue to stimulate vital directions in the history of art. And so the heartbeat of Klee lives on in posterity.

Norman Lewis, Untitled, 1947. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York.

1 Barr, introd. in “press release” (1931) for German Painting and Sculpture exhibition at MoMA, March 13-April 26, 1931, MoMA Archives.

2 James Thrall Soby, in Paintings, Drawings and Prints by Paul Klee (New York: MoMA, 1949), 10.

Ten Americans: After Paul Klee, co-organized by The Phillips Collection and the Zentrum Paul Klee, is on view at the Phillips through May 6, 2018

http://www.phillipscollection.org/events/2018-02-03-exhibition-after-klee

Send your own playlist based on works in the exhibition to communications@phillipscollection.org

#TenAmericans.

Elsa Smithgall is a noted art historian and curator at The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, with a specialty in modern American and European art. In the past decade, Smithgall has contributed to numerous publications and curated over ten critically-acclaimed special exhibitions. Among them are Ten Americans: After Paul Klee, People on the Move: Beauty and Struggle in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, Whitfield Lovell: The Kin Series and Related Works, William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, and Kandinsky and the Harmony of Silence: Painting with White Border.