THE BODY

Body Worlds

Fiction By Elizabeth Hazen

Illustrations by Rebecca Hsu

I’d been looking forward to it for weeks, thrilled that my husband’s law firm had given us tickets to the sold-out exhibit. Ever since learning about him in nursing school, I’d been fascinated by the German scientist Gunther von Hagens, who invented plastination and created Body Worlds. I’d followed the controversy around it with the fervor of a fangirl. He had to be mad but also a kind of genius, and I was drawn to those extremes back then.

“I just don’t understand the appeal,” my husband said.

“Aren’t you curious? Don’t you want to see what they look like?” I asked.

“Do I want to see a bunch of dead bodies? No, I can say with 100 percent certainty, I do not.” He was using his “professional” voice, enunciating with exaggerated crispness, and standing in the doorway in front of me with the prim posture of a choir boy.

“Well, I’m going,” I snapped, turning abruptly from him. And I knew he would too, though I would have preferred to go alone. He didn’t want to turn down the partners’ generosity, nor did he want them to think him squeamish or a prude.

—

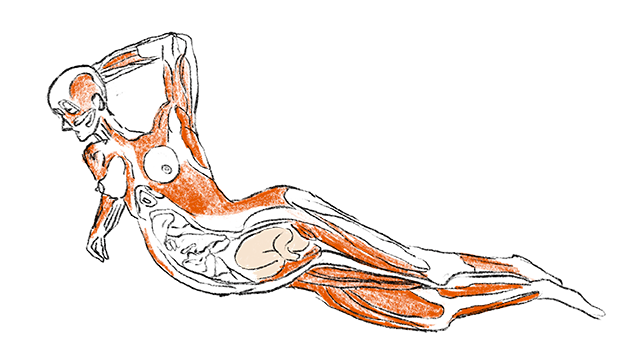

After waiting in line long enough to send my husband into foot-tapping mode, we finally reached the exhibit hall, a collective gasp running down the line like an audible version of “the wave” at a ballpark. The flayed bodies were everywhere, arranged doing ordinary things: sitting at a table playing cards, dribbling a basketball, swinging a bat, stretched out in dancer pose. A male stood tall, one hand by his side, the other holding his skin aloft, a cascading blanket of rubbery flesh. Most of the bodies were the earthy red of our musculature. Some opened themselves deeper so we could see the circulatory system, organs, or bones.

The scene was overwhelming and surreal. Living bodies filled the spaces between displays, and I kept thinking that underneath their athleisure and weekend khakis, they were indistinguishable from the figures all around us. I was distracted, too, by the body growing inside me, the one no one else—not even my husband—knew about.

We’d been fighting a lot lately—little spats like the one this morning. I was anxious but not ready to tell him why, so my fuse was short. None of the arguments were major, but the tension between us had become a partition.

I glanced at him to assess his reaction to the scene, but he had on his public face, the face that says, I am a responsible lawyer, I am a professional, a grown-up. He did seem pale, though, maybe even a little green.

—

My husband and I married young, just out of college. It had only been six years earlier but felt longer. When he proposed, I was taken aback. He had a ring and everything. Midnight on New Year’s Eve, our senior year. Down on one knee, the music paused, all our friends watching. What could I say but yes? And he stuck with me through some hard times. He supported me through the grind of nursing school and the crazy hours at the hospital. When my drinking was getting out of control, he held back my hair while I puked and was gentle while I tended to hangovers. He’s the one who finally dragged me to a meeting. But when I started to make noise about wanting a baby, he put on his paternalistic voice, his grown-man voice that always made me choke back laughter. He reminded me of those old cereal commercials with the little kids in adult-size suits.

He was emphatic. “We’re not ready,” he told me like that would be the end of it. “We can’t afford it.”

But my body was louder, more insistent. I wanted a baby. It had only been a couple of months since I’d gotten sober, but wouldn’t pregnancy be like an insurance plan? Better than Antabuse to keep me off the bottle. So, I stopped taking my birth control pills and didn’t tell him.

—

Already, my baby had a face, an alien face with huge dark circles for eyes. Already her heart (I was sure it was a her) beat sixty-five times a minute. She was smaller than a grain of rice. I knew it was bad luck this early in a pregnancy, but I ran through a list of names. I imagined living somewhere with a small garden and a house where she and I could paint the walls bright colors. My husband had always insisted we keep our apartment neutral—“So we don’t lose the security deposit,” he’d say. I tried pointing out that we could always paint it back later, but his response was emphatic: stop using energy on frivolous things and focus on something important. I’ve never understood what makes a thing “important.”

—

Nursing school had eradicated any squeamishness I had around bodies, though this scene was undeniably bizarre. These bodies weren’t on gurneys or in coffins; they were garishly mid-swing with tennis racquets or crouched in a runner’s lunge, waiting for a starting shot that would never fire. But even though I knew that these were actual bodies, they still seemed more like scientific models, not real people.

My baby didn’t seem real either. She was still in the sea-creature-looking stage on the fetal growth chart that hung in the obstetrics wing at the hospital, but she’d start growing limbs soon. Her systems—musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, respiratory, digestive—would start to form. She would have a heartbeat. She would grow to the size of a quarter, then to the size of the token I received after my first month clean.

—

I would have six months in another week. My drinking had never been a problem until a couple of years earlier. It happened gradually, the way so many things do, and then all of a sudden. I knew I had to quit after I came-to at the wheel of my totaled Honda Accord to find police lights and a woman in uniform knocking on my window.

My husband was furious when I called him, but he came to get me. He got the cops to let him take me home instead of to jail. I’m not sure how he managed it, but I guess those lawyering skills come in handy for more than just protecting corporations. He cried that night, begging me to stop drinking. He yelled, too, but it was the crying that got to me. And the way he held onto me so tightly, as if he were holding me together with his arms. As if, when he let go, I’d just fall to the floor in pieces.

He wasn’t wrong; I did need to stop. I was spiraling. At least no one had gotten hurt, I comforted myself in a meek defense I didn’t dare say out loud. Other things I never said: even sober I feel out of control. I feel like I am bursting out of my own skin, like I can’t contain myself, like if I had the strength I’d start running and keep going until I got somewhere far away, until I was free of this – what? I couldn’t articulate it. This loneliness? This restlessness? This body?

—

After acclimating to the bizarre scene in the exhibit hall I noticed dust settled into the plasticized arteries and sinews of a saxophone player. The saxophone, too, was dulled by a filmy layer of dust. I fixated on it. This careless submission to entropy—not the bodies themselves—

is what bothered me. Even if the bodies never decomposed, the world around them would carry on. Time would carry on, dust accumulating indiscriminately, the detritus of our skin, our breath, the mud on our shoes. I didn’t say any of this to my husband.

Instead, I asked, “What do you think? Pretty wild, right?”

“That’s one word for it,” he said, his voice a scalpel.

“Don’t you think it’s interesting? I mean, it’s pretty amazing . . .” I trailed off. He wasn’t listening to me. Not really. “Hey, you okay?”

“It’s just . . .” he started. “I don’t get it. I don’t get why you like this stuff. It’s morbid.”

He looked so young in that moment, the way he must have looked as a little boy. He was afraid. I wasn’t sure what to say, so I said nothing. That was how I handled—or failed to handle—things back then. I just let them alone, hoping they’d resolve.

I first met my husband in the dining hall at the college we both attended, late in my freshman year. It was a dim-lit, gothic kind of room, imitative of the grand buildings at Oxford or Cambridge. I was unhappy back then, dining alone on tiny meals of lettuce and olives that barely kept me going. One day he just sat across from me and started talking. It was nice having someone notice me. I was grateful. We started finding each other at every meal, and after a couple of weeks he asked me out on a date. Dinner and a movie. We had spaghetti and meatballs at this little restaurant a few blocks from campus and then saw a sci-fi action movie about a soldier who wakes up in someone else’s body and has eight minutes to stop a bomb. Neither of us liked it much, but afterward he walked me to my dorm and kissed me goodnight. After that, we were an item, and I felt like a different person, like the kind of person who has a boyfriend and a friend group and plans on the weekends. That was almost a decade earlier.

—

To distract myself from the dust, I focused on the signage around the exhibit. Later that night I filled in gaps with Google searches about plastination. After they pump the bodies with formaldehyde, they dissolve the messy parts in acetone, which is just nail polish remover. They lower the temperature and replace all the water in the body with nail polish remover in a process called vacuum impregnation. They also do this in industrial manufacturing—for motors and machine parts. The whole process leaves the bodies flexible, so they can be posed like dolls. It all seemed like something out of a sci-fi movie or dystopian novel.

The argument for doing this is that it’s educational; people donated their bodies so the rest of us could learn. But did they really want to be displayed like this? Holding up their organs like pieces of fruit? My husband wasn’t wrong about it being morbid, but more than that it was vulgar and tacky. Could these people have wanted to be posed sparring with other anonymous donors? Frozen in athletic feats they surely never accomplished in life? There was a display case with babies in all stages of development. I doubted they agreed to this. My baby was still too small to be displayed in a case.

My husband tugged my arm when he saw that I was frozen, fixated on the babies.

—

In two more months, she would have fingers and toes. She would open and close her mouth. Her fists. She would have fingernails and ears and calcified nubs of teeth. She would produce bile and be as big as the palm of my hand. If we had returned two months later, I might have seen her behind the glass, filled with acetone, not moving. Not opening her mouth.

My husband opened his mouth and then closed it without speaking. He did not reach for my hand. People watching us might not even have known we were together, just like people watching us didn’t know that my baby was inside me, getting ready to swim around.

It is only when we got to the case with the puckered, sallow liver beside a plump, healthy one, that my husband glanced my way. I read it more as a “look what you’ve done” glance than anything supportive, though in retrospect I think it was probably anxiety I was sensing more than judgment. I was defensive about my drinking. I didn’t like to be reminded. I had almost six months at that point. I had a baby inside me the size of a coin. I didn’t want to look at a dead person’s cirrhosis, but I didn’t want to explain all this either, so I tried to look contemplative, contrite.

—

By the second trimester, my baby would start to have a face, complete with eyes and ears. She would be able to hear my voice. Her fingers and toes would separate, and she might even suck her tiny thumb. She’d grow layers of protection: soft fur, a slimy coating. I’d know for sure if she really was a she. She’d swim and play inside me. When I spoke to her, she’d hear me. She’d grow and grow and I’d grow to accommodate her. There would be no hiding the fact of her.

—

My husband seemed to be trying to move more quickly though the exhibit after the diseased organ display, and he was pale—I was certain now—but there were so many people, it was difficult to push through the throngs, so mesmerized by the fish-eyed mummies, the frozen ghosts.

We didn’t find out much about who they were. There were multiple assurances in the literature that the bodies were willing participants who donated themselves to science, who agreed to be flayed and spliced and held open with glue and pins. Or they were prisoners whose crimes had resulted in their loss of agency over what would happen to their bodies. I suspected this was the majority.

But the dust! I couldn’t stop myself from seeing the thin layers of dust, the nicks, and loose hinges on the bodies. I know they were dead, filled up with formaldehyde and plastic and really were hardly human anymore anyway, but I imagined them exhausted. I resented the curators for taking such shoddy care of these bodies, for failing to keep them clean.

One held himself open as if he was Clark Kent ripping free of his button-down shirt to reveal his Superman outfit, only it wasn’t a shirt but his skin, and it wasn’t a big “S” on a blue background, but a web of arteries and musculature and organs.

Without skin over their sockets, all of them were bug-eyed.

—

The last step before they put the bodies on display is the hardening or curing. It can be done with gas or light or heat. It prevents decay. All these corpses mummified, posable, transformed from flesh into plastic. Two men played chess. A woman danced. A pair of bodies fenced.

The total process takes fifteen hundred hours.

—

A few years earlier, we’d had a pregnancy scare. Neither of us wanted a child at that time. I was mid-way through nursing school, and he was preparing for the LSAT. When I realized I was three weeks late, I panicked. I didn’t know what I would do if I really was pregnant, and I waited another week before I said anything to him. When I did tell him, he was resolute. You’ll need to have it taken care of, he told me. I’d been thinking the same thing, had even looked up clinics near us, but hearing him say it so authoritatively, like it wasn’t my decision too, made me angry. I think that’s when something broke between us.

In the end, I didn’t need to do anything; my body made the decision for us. The bleeding was heavy and lasted a week. We didn’t really talk about it, but for months the loss lingered between us like a ghost we both pretended we couldn’t see.

—

Near the end of the exhibit, I swallowed a gasp. A woman lounged on her side, propped on her elbow, belly cut open to reveal a baby ready to be born, tucked inside her. Later I researched this woman who learned of a terminal illness while pregnant and agreed to donate her and her baby’s bodies.

My husband beside me didn’t try to stifle his disgust. “Jesus,” he said. And then, “We’re leaving.” He spoke in anger, but there was fear wavering underneath.

By the time the woman died at eight months pregnant, her baby would have been able to live outside her womb. It had developed enough. But maybe the baby was sick, too. Maybe it was too late to save her.

I don’t know why exactly this was the moment I chose. Why this was the moment it all became too much, why this was the place I decided to dig in my heels. But I didn’t want to leave yet, and I was tired of being told what to do. I was calm about it, speaking quietly. Only the people right in front of us and right behind us could hear.

“I’m not leaving yet,” I said. “You can leave, but I’m staying here.”

I didn’t say the rest out loud right then, but I knew I would later when I got home.

Elizabeth Hazen is a poet and essayist. After teaching secondary school English for twenty years, she changed tack and currently works at an independent bookstore. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Best American Poetry, EPOCH, American Literary Review, Shenandoah, Southwest Review, and other journals. She has published two collections of poetry with Alan Squire Publishing, Chaos Theories (2016) and Girls Like Us (2020). "Body Worlds" is her first published fiction. She lives in Baltimore with her family.