Fear of a Black Superman

Discovering the power of narrative in the superhero mystique

by Alexander Ramirez

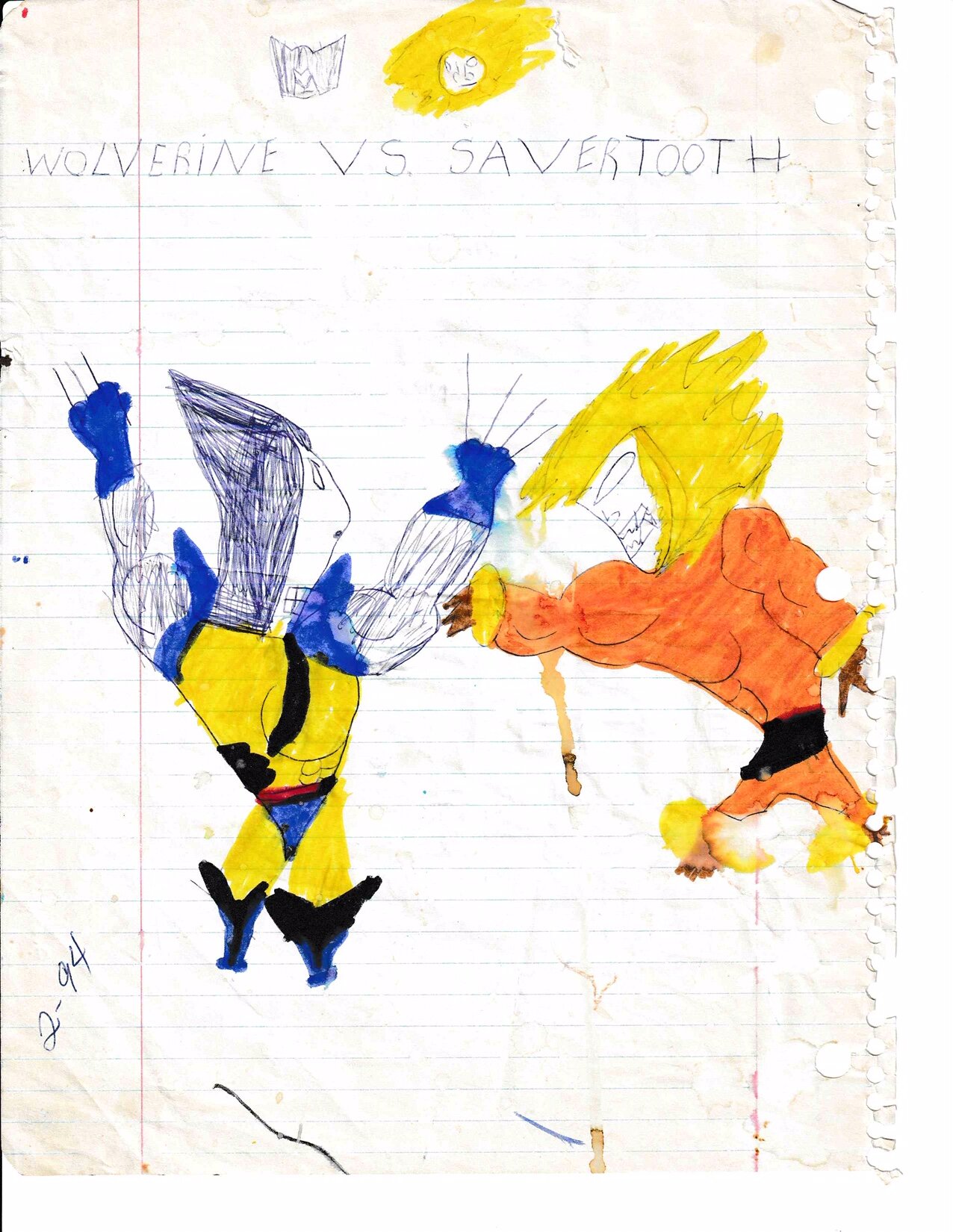

Courtesy of the author

I was four years old the day Superman died. He was beaten to death by a hulking golem from outer space, and the event shook the world. News vans parked outside of specialty stores across America. My mother doesn’t remember waiting up for our local affiliate to air their segment, but I do. I remember that my father left us a blank VHS cassette to record it before he went to work. He had been among the collectors accosted by field correspondents for an interview. He had been among the millions[1] who’d descended on their local comic shops in reverence, who’d come to pay cash tribute for their allotted copies of Superman #75.[2] The collector’s edition of the issue had been sealed in an austere polybag. The iconic S-shield had been transmogrified in a field of funereal black. The face of the artifact dripped with gore.

In the comic book’s final pages, Superman and the space golem called Doomsday both lie dead. Lois Lane, her cheeks streaked with tears, cradles the hero’s limp body in a bed of rubble. The blood pouring from his body is so thick that the inks used to render the carnage appear black.[3]

I began drawing his tombstone[4] often after that. It was something I did whenever I drew a picture featuring a plot of grass. With whatever pens or pencils I could find around the house, in the junk drawer or between the couch cushions, I would make sure to add Superman’s final resting place to the scene. I would drag my writing tool up, over, and down, so that the streak I left behind began and ended at the horizontal line denoting the lawn. I then filled the arc I had just created with his S-shield. Rows of squiggles underneath suggested an inscription on the stone. In my mind, the presence of the memorial added verisimilitude to the illustration the same way straight lines around a circle transform meaningless scratches into a depiction of the sun. Even then I recognized that the lifeblood of storytelling was vivid detail.

Courtesy of the author

But I didn’t read many books as a child. I wouldn’t read the novels assigned to me in school. The stillness and concentration that accompanies the act of reading made me anxious, and my mind would often wander from the text as I read along, retaining next to nothing. My parents were active readers when I was younger, and my father remains one. He reads voraciously, compulsively, as if to store away the information lest it vanish from human memory forever. The impulse he acts upon when he reads is the same one that has driven him to amass and store his vast collection of comic books[5] over the past five decades; it is also this same impulse that told him to leave us the blank VHS with instructions to record the newscast on the day of Superman’s death.

This is not to say that I avoided literature all together. I did have a small comic book collection, many of them hand-me-downs from my father. I always read the box scores on the sports page and the movie synopses in the television channel guide that came with the newspaper on Sundays. At some point, I was given a used dictionary—maybe I was five or six—and I took to reading and rereading definitions as a pastime. But because of my early aversion to most literary fare, my mother sometimes considered me an aberration, or a changeling—except that I made illustrations so often. She saw that I preferred to create the story myself. I drew pictures in the margins of the phonebook. I drew pictures on recycled stationery. I drew in my mother’s spiral notebooks where she kept handwritten recipes and balanced the checkbook. She says I was two years old when they stopped having to ask me what I was drawing. I could render recognizable figures before I could formulate complex sentences.

In photographs from that time, the pens I’m holding are almost as long as my arm. If you ask my mother today, she’ll describe my drafting skills then as something approaching the preternatural. She’ll be exaggerating, of course—wildly—but I did exhibit a rare interest. My parents were proud. Their first-born was artistic. So it did not give them pause when, over and over, I would draw Superman’s bleeding, dripping S-shield in startling red ink.

On the school bus, when I wasn’t sketching some original superhero, I would look through the glossaries of my science and history textbooks, combing the back pages for dynamic code names for my characters. Sometimes, the definitions were enough to inspire their powers. During the presidential election of 1996, I remember participating in a mock vote in class. I checked the box for Bob Dole because I preferred the sound and dictionary definition of “republican” to “democrat.” The teacher told us that we were choosing who would become “the most powerful man in the world.” I tilted my head at the claim. I didn’t know politics, of course, but I knew there were characters with superpowers. I knew comic books.

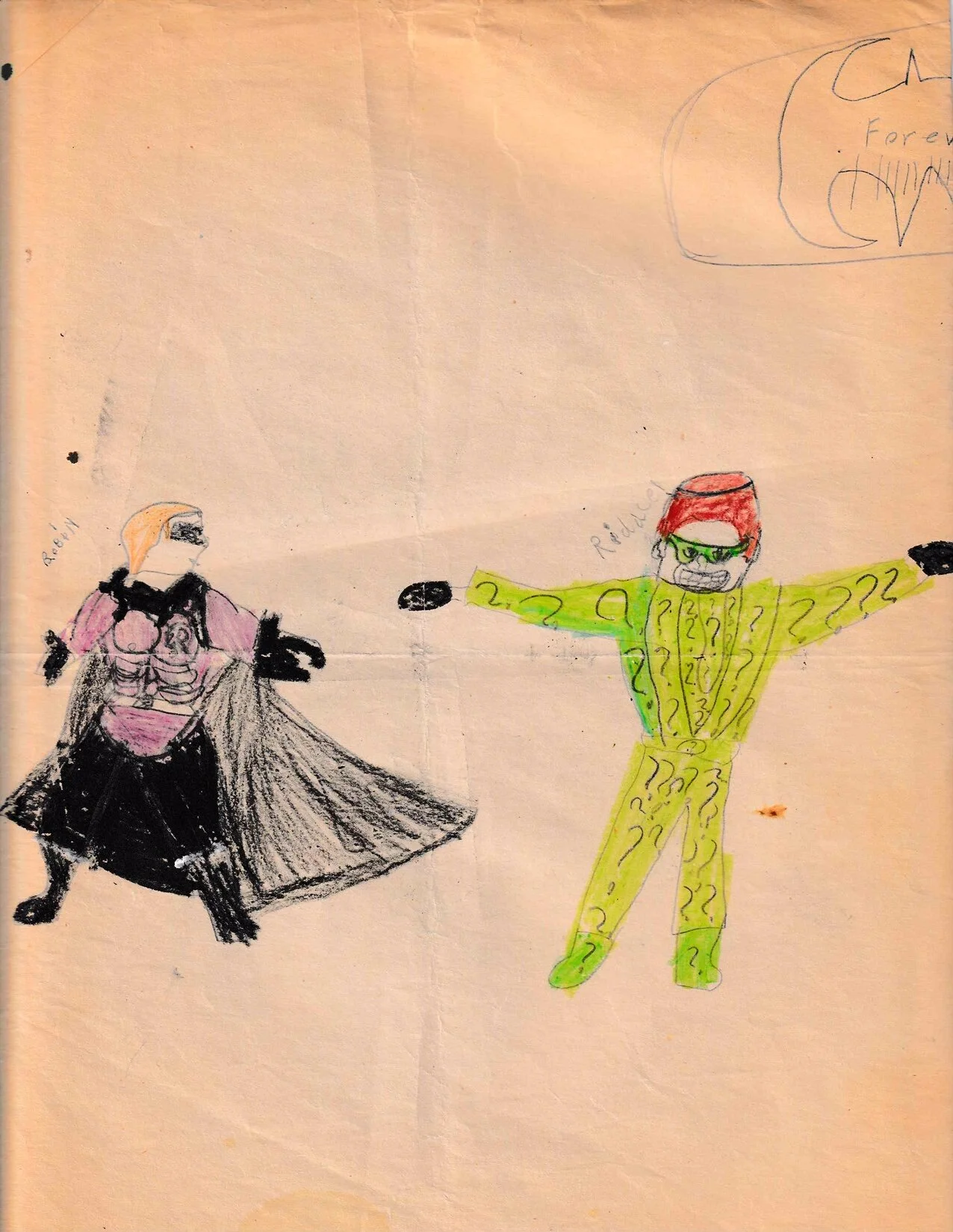

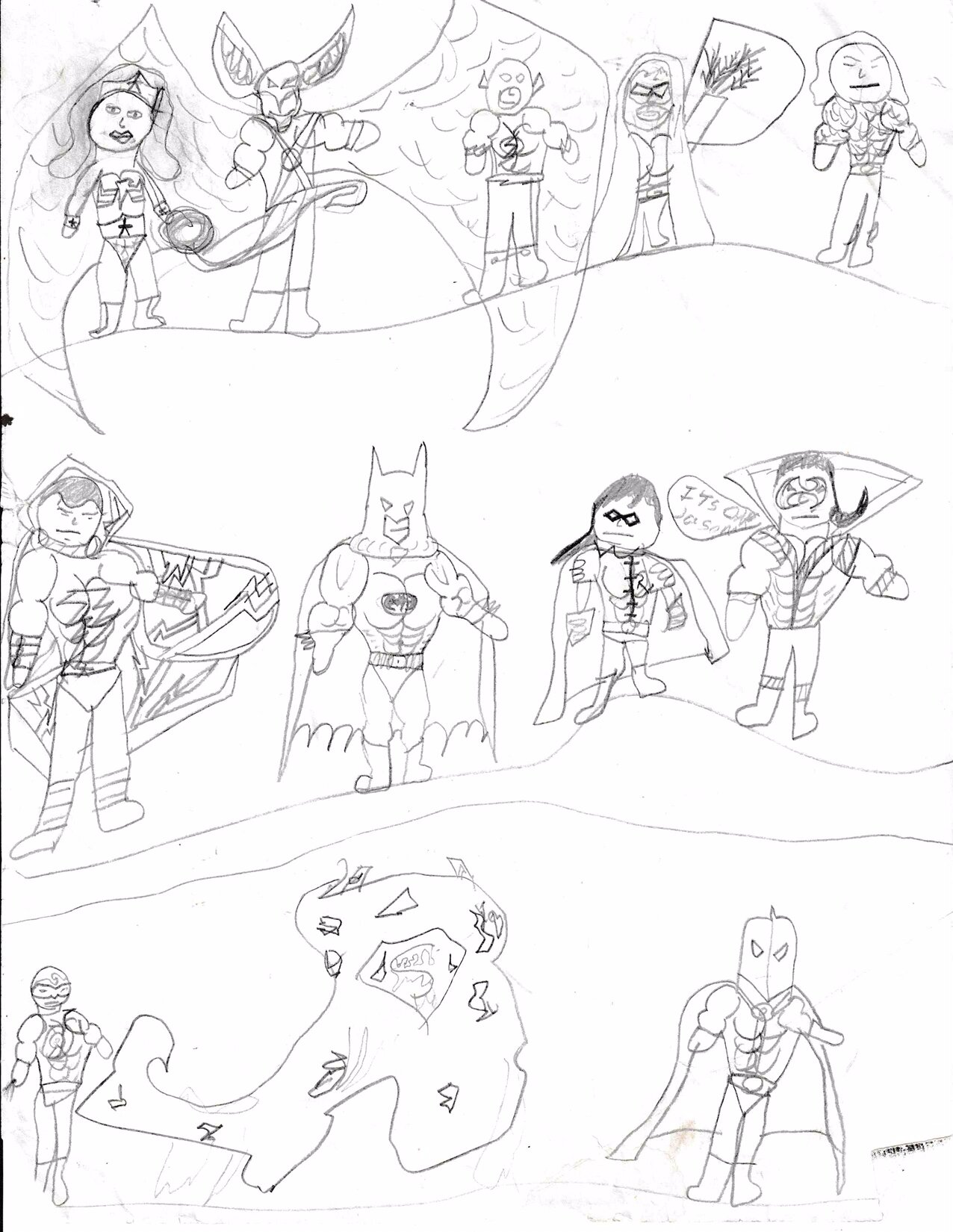

Bam and Boom were the first superheroes I ever created. I didn’t need a glossary for those names. They were Batman and Robin, essentially. Both men were muscular and athletic. Both were devoid of superpowers. They were crime fighters who wore matching eye-masks, light blue spandex, and capes, and they always settled matters with their fists. And, perhaps as consolation for their lack of x-ray vision or super-strength, they always knew exactly who to punch.

Courtesy of the author

In the third or fourth grade, I created a Superman analog in class. The teacher was probably discussing an assigned story I hadn’t bothered to read, so I drew the figure of a man on my binder paper, statuesque and all-powerful. I named him Ghostman because he was already dead—and, probably, because I had modeled the white body on Alex Toth’s design for Hanna-Barbera’s Space Ghost. Ghostman flew and threw punches like Superman. His cape was blood-red. And the character didn’t have a face. Instead, he’d sewn a dingy, once-white oval of burlap or some other textile over the profound crater at the front of his head. He’d used a thick length of twine to do it. He’d also cut a pair of obtuse triangles into the material to suggest there might be a pair of eyes behind the cloth. Ghostman was an anti-hero for the nineties, not untouched by the popularity of characters from the Image Comics[6] imprint, especially Spawn. He was my Superman analog. And he could not die because he was already dead.

As a four-year-old, I learned that our local media—and the whole country—would pay tribute to Superman. Comic book superheroes had achieved mainstream relevance in the Hollywood cinema with Superman: The Movie (1978) a decade before I was born. They then began their slow crawl toward ubiquity with Tim Burton’s Batman (1989).[7] Movie serials, live-action television series, and Saturday morning cartoons had conspired to keep superheroes afloat in the pop culture milieu since the 1940s. But the literature, the monthly magazines from which it all sprang, was always relegated to the margins of public consciousness. Comic book collectors, like my father and me, were oddities, a community of dreamers and mythmakers, summarily branded as immature, silly, stupid. That a news program would be reporting on the books, not the movies, was enough to send me looking for a clean sheet of paper to draw on. That my father would appear on television as an emissary for our subculture was sublime.

But as my mother and I sat in the living room, watching the newscast, the last vestige of sunlight sank below the horizon outside. The only light in the room emanated from the television. When the program cut to commercial, we were left, for a moment each time, in total darkness. I soon realized that the Superman segment would be pushed to the end of the broadcast with the rest of the day’s dregs. I looked out the window, and the night was black. My bedtime was approaching. The VHS my father had left us, already loaded into the VCR, simply idled inside the machine.

When my mother told me that it was time for bed, I protested. I did it tactfully. Never mind Superman, I implied: my father hadn’t appeared on screen yet. But she wasn’t swayed. It was late. I could watch and re-watch the recording any time, she said. So, I padded down the hallway, dejected. And my reluctance to go to bed that night taught me something that remains with me to this day. I believe it’s shaped my life and led me to my career. Though I was incapable of intellectualizing it at that age, I understood it—in my heart—all the same. I knew that although Superman was dead, he wouldn’t remain that way for long.[8] Kings and pharaohs are entombed with gold. Dead presidents lie in state. But gods, like Superman, are committed to literature for posterity. I was hanging my head as I marched to my bedroom not because I wanted to mourn my hero; I only wanted to stay up to bear witness to history. I would one day choose storytelling as my vocation because I didn’t regard death the way so many others do. A traditional funeral has speakers at the viewing, eulogies at the pulpit, and informal commiserations at the wake. A funeral is supposed to collect and extend the story of a life. And less than a year after his bloodied body had been drawn and inked and colored across a stunning gatefold, Superman emerged from the plasma of an alien birthing matrix.[9] In Action Comics #689, he lived again. And ever since the death and resurrection of Superman, I’ve known precisely what happens to all of us when we die: we become stories.

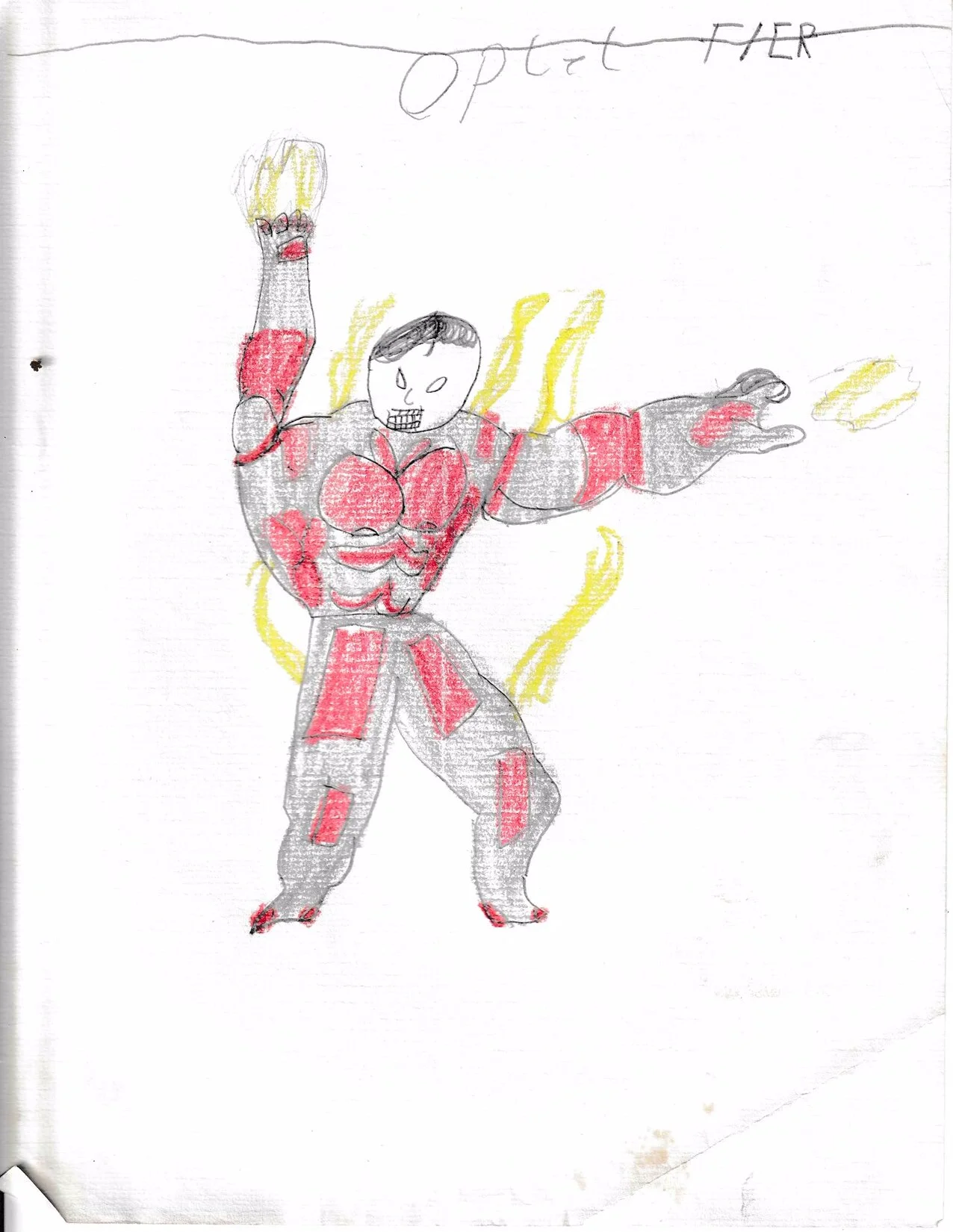

I drew the characters that monopolized my attention. They lived in my head and kept me up at night, so I set them on paper in ink and graphite. I freed them. I drew a helmet with a visor inside the back cover of a spiral notebook. I drew a chin beneath the visor and a neck beneath the jawline. My father had rented Judge Dredd (1995) on VHS not long before, and I was so taken by the character’s design and iconography that I decided it was beautiful enough to steal. I added stubble to the jawline. I hid his body behind a massive, wind-shot cape, a trick I’d learned studying the ways that Todd McFarlane and Greg Capullo would sometimes draw Spawn.

I created a scientist who’d been transformed by his chemicals in a laboratory explosion. His cowl was appressed to his scalp and widow’s-peaked, like those of the pulp heroes from the interwar period. The scientist’s body had been electrified in the explosion, a terrible accident that may not have been an accident at all. Now, he could summon webs of electricity from the core of his being to aid him in his newfound mission to right wrongs. I added snakes of lightning that crackled at the edges of his eyes,[10] but I didn’t give him a chest logo.

On the school bus, I drew a ninja in repose. I named him SASO; I suppose I thought that to be a proper name for a katana-wielding master of ninjutsu. I based his mask on a melding of the luchadores I knew. I drew his hair long and imagined his costume as a red-and-black bodysuit. When I was finished, because of the mask, I saw that SASO resembled a ponytailed Spider-Man. I gave him a brother, a villainous one, named Samson. Samson had long hair, too, of course, and he wore a smooth, white mask like Vega from Street Fighter 2. I tattooed his arms, like the bad guys in Yakuza movies.[11] These brothers had been raised and trained by their grandfather, I decided, and what a tragedy it was that Samson had gone astray, had chosen a life of crime over a life of goodness and discipline. But, thankfully, wherever Samson went, his younger brother vowed to be there to honor what their grandfather had taught them.

It was always a relief to see a character take shape before my eyes, but drawing wasn’t enough as I got older. Linework couldn’t express the nuance of my characters’ histories and struggles in a way that I judged to be comprehensive. I started reading more as a teenager, and it was as if my compulsions had switched from one practice to the other. I read novels and screenplays, stage plays and poems. I read comic books more than ever. I began purchasing the trade paperbacks that collected story arcs from the monthlies. By the time I was eighteen, I decided that I should tell stories for the rest of my life. I bought books to teach myself about screenwriting.[12] I tried my hand at writing a short script,[13] and I finished it in a day because I did nothing else. It was an awful attempt, but that didn’t matter. It was out of my head. It was alive on the page.

Courtesy of the author

I decided, because I was apprehensive about my dream job, that academia would be the most practical way to achieve my goal—to become a writer, whatever that meant. I enrolled in community college as a film major before eventually switching to English. I was told that becoming a serious writer would be hard work, and that was fine with me. I was already accustomed to hard work. That only made the goal seem attainable.

I’d worked as a cook and a caterer alongside my grandfather for almost three years beginning when I was fourteen. We rose at five or six a.m. on the weekends and cooked hundreds of pounds of carnitas in oversize copper pots. Once, he splashed me with a dime-sized dollop of caramelized sugar; the skin on the back of my hand floated away like a wafer, and I trembled with fever that whole night. Another time, when I crouched to light the pilot beneath the cazo, propane flames raced up my arm and toward my face, singeing the wisps of my mustache. I was excused from serving at the event later that night, and I sat in my mother’s living room, drinking from a bottle of tequila. Weeks later, when the boils that stretched from my knuckles to my cuticles deflated, the doctor debrided my hand. The flames left no noticeable scarring, but the caramel splash on my left hand still looks like a cigarette burn. I took the cash my grandfather paid me and bought the first trade collections of Preacher and The Sandman and the hardcover edition of Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale’s Superman for All Seasons.

When I was sixteen, I became a banquet server for sister sites in downtown Sacramento. I worked weddings and fundraisers and political caucuses in a hook-and-loop bowtie. When I was eighteen, I became a busboy and, later, a waiter. By that time, I had devoted my education to English literature, and it was time to transfer to Sacramento State.[14] The significance of my chosen discipline was not lost on me. I have always been able to speak English, but when I began doing it often—in the early nineties, I’m told, a year or two before Superman died—I did so with a noticeable accent. I remember snatches from that time, but I don’t remember the sound of my own voice. In any case, that boy would earn a master’s degree in the language of his family’s adopted country.[15] That boy would become a doctoral student and earn the right to teach English at the University of Nebraska. During my first summer home from UNL, on Mother’s Day 2018, I sat on my mother’s patio and drank with my grandfather—a naturalized US citizen who is quickly forgetting all the English he’s accumulated. I asked him if he remembered burning my hand with sugar. He asked me, his eyes red and wet, if I knew that all his life’s work had been so that I could be whatever I wanted. He mentioned my grandmother, his wife, who died at the age of twenty-nine, the same age I was when I began my doctoral program. He asked me if I knew that she had been a teacher in Mexico. I asked him if he knew that I loved him. And we sure as hell did not ask each other these questions in English.

I’d worked more than a decade, uninterrupted, in the service industry, waiting tables while I juggled school and, usually, something else part-time. I scrubbed tables and drove forklifts. Before leaving for Nebraska, I had my most secure job as a copyeditor for California’s Office of Legislative Counsel. I left it all behind for a chance at a Ph.D. And none of it—not any of it—has been more difficult than the job of writing. And that, I believe, is precisely why I write. I understand that many people who find purpose through their profession feel the same way, but I believe that what I do for a living is the most essential thing in the world. Everything that a culture understands about itself, it understands through narratives. Consider how even the sporting events that we watch passively are dramas. They’re divided into periods or innings or quarters that may as well be called acts. The ball (or puck or whatever) is a concretization of desire. Opposing teams want it, need it to achieve their preferred version of resolution. The winner is, essentially, the side determined to be the most effective narrator of the action. The hero. The victor brings order to chaos. Ursula K. Le Guin, the great American novelist and essayist, said that history is rife with examples of civilizations that got along just fine without the advent of the wheel, but that none have ever survived without storytelling. That is why I love what I do. Writing is the most significant thing I’m capable of doing within a society. There must be raconteurs. There must be stories. It is a service, and so, as far as I’m concerned, I never left the service industry.

I stayed at Sacramento State for my master’s degree, taking night classes alongside other students tired from their workdays, because a writer and photographer named Doug Rice taught fiction writing and film theory courses there. Professor Rice is an East Coast scholar, originally trained by Jesuits, who was educated at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and SUNY-Binghamton. At the latter institution, he became a disciple of John Gardner, the author of Grendel and an indispensable craft book titled The Art of Fiction. It was from Gardner’s lectures at Binghamton that the craft book emerged. Today, I assign the text to my undergraduate fiction writers at my university.

Courtesy of the author

The book argues that aesthetic universals do exist in fiction, but that aesthetic laws operate “at such a high level of abstraction” that they are incapable of leading the writer by the hand. Laws vary from story to story. It’s as if each piece of new writing is a new lifeform entering the ecosystem, and the process of writing and rewriting is its necessary evolution. Structures and stratagems must enter the wild of the blank page[16] to live and die until one develops the proper latticework, the correct sequence of bone formations, or the ideal exoskeleton for survival. The writing must attain a level of fitness, and there is no way for the writer to achieve their goal, to communicate their story the only way it can be communicated, other than trial and error—through work and more work.

Professor Rice would sometimes tell us about the nights that he accompanied Gardner and another of Gardner’s students, the short story maven Raymond Carver, to bars on the East Coast. While Carver and Gardner drank and smoked and talked, my former professor says that he ordered club sodas with lime. He scribbled notes on his writing pad. He watched. He listened. He learned. He regards stories the way I do because he regards work the way I always have. On days I don’t write, my unfinished stories haunt me. I always know that the one I’m working on is at home, waiting for me by my writing desk. And when I walk in the door, too exhausted or too busy to attend to it, it gawks at me and breathes audibly, a slack-jawed Bizarro[17] whose face is desperate to attain the lantern-jawed handsomeness of a Clark Kent. The monster eyes me. Too often, I ignore it and slink off to bed. The last time I went to sleep without first reshuffling the pieces of a nascent story in my mind, I was still a teenager. The next time I know that peace, I assure you, I’ll be either demented or dead.

Because of all this, my education and my upbringing, I think about Superman quite a bit. I reflect on his legend, his ever-expanding, ever-changing mythology. I refer to him as a “him” and not an “it.” His story, after all, is real to me. By its very nature, its serialized form, it can never be finished, and so it haunts me every day.

Jerome Siegel and Joseph Shuster were teenagers when they first collaborated on the character. They were both sons of Jewish refugees. Together, they constructed an origin story that now lives somewhere in the ether of popular imagination. On an alien planet facing certain environmental destruction, a scientist and his wife decide to send their infant son into outer space to save his life. They load the baby into a rocket ship and launch him through the starways. When the ship crash-lands on Earth, the boy is discovered and adopted by farmers in Smallville, Kansas. The earth’s yellow sun enhances the child’s alien biology, and the boy becomes a man and eventually a hero on his adopted planet.

Courtesy of the author

It’s no coincidence that Siegel and Shuster named their character Superman. It’s almost a platitude at this point in the character’s history, but I’ll repeat it here for the uninitiated: Adolf Hitler appropriated Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch[18] to prop up his theory of an Aryan master race.

Michael Uslan, the man who taught the world’s first accredited college course on comics, convinced the skeptical dean at Indiana University to approve the class by asking him to recount the story of Moses. The dean recalled how a Hebrew couple loaded their first-born son into a basket and sent him down the river Nile to save his life. The dean remembered that the baby was rescued by an Egyptian community that noticed the basket floating on the water. Moses would be raised among them and become a great hero. When Uslan reminded the dean of Superman’s origin story, there was nothing left to do but approve the syllabus on the spot.[19]

Siegel and Shuster’s first Superman story, from Action Comics #1, takes aim at men who beat their wives and men who accost women in social settings. “You’re not fighting a woman, now!” Superman says to a wife-beater while dispensing swift justice.[20] And later, when three brutes kidnap Lois Lane because she refuses to dance with one of them at a party, Superman chases down their car, shakes them out the windows, and accordions the vehicle’s chassis against an outcropping beside the highway. The character was, from the very beginning, a “Champion of the Oppressed.” Siegel would write that very title into captions and dialogue balloons. Superman has always had the power to punch through any physical or metaphorical barrier. The creators made it a point to concern their contribution to the literary canon with justice of an overtly social nature. There are core characteristics that define any mythology, but a story that goes on for over eighty years, as Superman’s has, does not survive without adapting to the inevitable shifts in the culture that allows it to thrive. It’s quite simple: all things that are alive must change with their environment, must adapt and develop with the times, or else cease to exist. Even Superman’s archenemy, Lex Luthor, has evolved from an archetypal mad scientist to an unscrupulous business magnate. Following the controversy surrounding the 2000 US presidential election, the artists at DC Comics were inspired to have Lex Luthor run for president in their books.[21]

In the hands of the best artists and writers, Superman provides a prism through which we filter new ideas and modern dilemmas. He’s a barometer of sorts. We change him to ensure his measurements remain precise. His stories have functioned as methods of obtaining data. Findings are reported by the way his adventures are resolved. The Aristotelian scholar James C. Raymond argues that “Rhetoric is a philosophical assertion that some important questions cannot be answered by experimentation, or by logic, or by quantification.”[22] And for a certain social class, Superman serves this purpose. We need him, it seems, to decide what ideals are valuable in an ever-changing world. Truth, Justice, and the American Way have kept Superman alive since 1938. So, how do these values hold up in new contexts? What should we let go, and what should we hold onto? What would Superman do? Who should Superman be?

In the late 1970s, when Superman: The Movie was being cast, the producers briefly considered the heavyweight champion of the world, Muhammad Ali,[23] for the titular role. He was not awarded the part, and ultimately, there was one primary reason that disqualified him from contention. Similarly, in the late 1990s, and at the height of his box office popularity, the producers of Tim Burton’s ill-fated Superman Lives briefly considered Will Smith to star. Just as it was with Ali, we know exactly why Smith never really had a chance. And today, in the wake of Henry Cavill’s dismissal from Warner Bros. Pictures’ most recent iteration of their Superman movie franchise, there are calls—at least among a small contingent of fans—for Michael B. Jordan to wear the cape. This comes after a pair of memorable performances in Black Panther (2018)[24] and Creed II (2018). But Jordan will not be cast as Superman any time soon. When confronted with the idea of a black Superman—or, really, any non-white depiction of the character—the opponents of change[25] are dogged and diligent.

Courtesy of author

Superman is a rural farm boy, they say, from Kansas. But black people work on farms, and black people populate the state of Kansas. They say that there is something to be said about preserving the iconography of a character that has endured for almost one hundred years. But the very S on his chest—the character’s logo—has been a site of tremendous change. What was once a simple initial representing his heroic sobriquet has evolved and become accepted, in turns, as the family crest of the House of El and the Kryptonian symbol for hope. Most recently, the Superman film franchise, following the lead of the comic books, made a conscious choice to erase the red trunks he’d worn since his first appearance. They said it was a new world. They said wearing red underwear over blue tights was silly and outdated. These alterations to Superman’s history and iconography were not unanimously embraced, but they did happen. And they became part of his mythology. And he is still Superman.

They will say nothing about how, originally, the character could not fly. For years after his first adventure, Superman’s legs were merely powerful enough to “leap tall buildings in a single bound.”

And, finally, they will evoke the word pandering. They deploy this word whenever representation in popular culture is discussed. They say that changing an established character’s race only serves to give the illusion of inclusivity. It’s a money-grab, they say. It’s exploitation of the highest, most obvious order, and therefore racist and wrong. They say, What if we made Black Panther a white man? What if the next Martin Luther King Jr. biopic casts a white man—or a white woman—in the lead? And they are either missing the point or ignoring it. Certainly, race matters when it comes to Superman in the same way it matters for Black Panther. Everyone agrees that T’Challa of the African nation of Wakanda should remain a black man; if that were to change, so would everything that makes him the provocative and engaging character we appreciate. In that same vein, then, Superman ought to retain his racial identity. And Superman is Kryptonian.

Why, then, should Kryptonians have white skin?

One of the poles of any theory of fiction worth reading is verisimilitude. If red underwear can disturb the fictive dream, then why do we still accept that an alien from outer space would share a phenotype with this country’s dominant social class? Superman's story can only become more complex, more interesting, if you complicate the way he appears to the world.[26] He is the Champion of the Oppressed, after all. The leader of the Justice League of America. At times, the character has inspired apathy because his powers render him, essentially, a god on earth. It has proved a challenge for filmmakers in the twenty-first century to raise the stakes for him without deploying trite narrative devices or departing from Siegel and Shuster’s vision. Of course, it’s been a long time since Superman was depicted in the comics as an inspired riff on the myth of Moses. The Man of Steel was appropriated by the Christian values of this country many years ago, and he has existed as a thinly veiled Christ-figure ever since. Superman first died for our sins in 1992, and the story of his death has become a multimedia trope. So, you see, I don’t exaggerate when I refer to the character as a god. And I know what I’m talking about when I advocate for change.

Tell me why, when I was a boy, I only thought to create superheroes who were white.[27]

I knew of Marvel’s Black Panther back then. I owned issues of Luke Cage, Power Man. Still, I drew monsters and aliens and robots. I drew anthropomorphic animals and the undead. It didn’t occur to me to create a superhero of color. I don’t think it occurred to me that I could. Even when I drew bystanders in an action scene—even when I based them on my father, giving them his mustache and hairstyle—they were never Mexicans like us. The superheroes between Marvel and DC were innumerable, but there was only one Superman. There was only one Batman. There was only one Spider-Man[28] and Incredible Hulk and Captain America and Wolverine. And they were all white men. In my young mind, superheroes—the ones who mattered, the ones with power—were white.[29]

Sometimes, when confronted with the idea of a black or brown Superman, the opponents of change simply say, He should stay white. And that is when they are at long last being honest with everyone. Superman should stay white, they say, and the statement is not far removed from the mid-twentieth century cries of, This water fountain is whites only! or, This diner should stay white! We already know they’re willing to alter his iconography. We already know they’re willing to divorce him from the vision of his creators. So, consider the evidence of your eyes and ears: they’d kill him before they’d imbue his skin with melanin. They’d rather his skin were electro-blue. And that proves to me that they know the power of storytelling as well as I do. Implicit in the idea that the character is somehow inherently white is the troubling notion that if he were any other color, he couldn’t be super. He could barely be regarded as a man. It’s all too obvious that they consider whiteness an integral part of the archetype, like capes and strength and—my god—the ability to fly.

Courtesy of the author

[1] The issue would, ultimately, sell more than six million copies.

[2] The demand for the issue was extraordinary. Many retailers across the country, including the one my father went to, set a limit on the number of issues they would sell to each customer. Comic book collectors and non-comic book collectors alike were convinced that Superman #75 might put their kids through college. Today, you can find the collector’s edition on eBay for less than twenty dollars.

[3] That’s how I remember it in my mind’s eye. But the actual inks used were, are, and always will be red—the same shade used to render the hero’s cape.

[4] As pictured in advertisements for SkyBox’s Doomsday: The Death of Superman trading card series. The inscription on the stone reads, “Here Lies Earth’s Greatest Hero.”

[5] As a teenager, when my father saw me reading Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen for the first time, he told me that the end of that maxi-series (1987) coincided with my conception. He said he stopped being a religious reader of the comic books he bought and stored after that. I believe he meant to tell me something about responsibility, but what I heard was that my life ended an aspect of his that he’d once loved.

[6] Image Comics was founded in 1992 by a collective of superstar artists. The creative enterprise was unprecedented in the comic book industry. Their aim was to establish a venue for creator-owned titles outside of the so-called “Big Two,” Marvel and DC. Simply put, under the Image banner, creators could publish original material and retain the copyrights to their own creations.

[7] This, I am told, is the first movie I ever saw in a theater. I was fourteen months old. I did not fret or cry.

[8] Characters often die in superhero comic books, but rarely do they remain dead. Roughly four years before Superman’s death, DC Comics garnered national media attention by killing Jason Todd, the second Robin. The character, surprisingly, would not be resurrected for seventeen years; when he was, he returned as the second Red Hood, a mantle that had once been held by his murderer—the man who would eventually become the Joker. Jason Todd had been introduced because the first Robin, Dick Grayson, outgrew his role as Batman’s sidekick and rebranded himself as a solo hero named “Nightwing.” According to canon, the name “Nightwing” was taken from legends of a Kryptonian vigilante. Grayson, who battled alongside Superman as a boy, paid homage to the Man of Steel by adopting a moniker used by a long-dead hero from his planet. Sometimes I tear up imagining the original Boy Wonder staring up at his hero, the immigrant god, as they fight for justice side by side.

[9] His dead body, apparently, had been recovered and attended to by Kryptonian machines that served as custodians in the Fortress of Solitude.

[10] In the late nineties, Superman was redesigned. This short-lived “Electro-blue” version of the character had eyes that leaked energy and a new blue-and-white bodysuit. At some point in the comics, the earth’s sun (the source of Superman’s abilities) went out; when it was reignited, his powers returned in this bizarre way. The S on his chest was now a stylized thunderbolt. He didn’t wear his iconic red cape anymore. Curiously, the artists at DC decided to tint his skin blue, too. The electric motif was a late-nineties conceit. I chose not to color my character’s flesh with a blue pencil, but I did take inspiration from this new-look Superman.

[11] In the first Punisher movie, released in 1989, Dolph Lundgren went to war with the Yakuza. Lundgren also battled the Yakuza in Showdown in Little Tokyo (1991), an action vehicle that co-starred Brandon Lee, son of Bruce and star of The Crow (1994). Rest in peace, Brandon Lee. Rest in peace, Bruce Lee.

[12] Syd Field’s classics.

[13] The script I wrote focused on a day in the life of an obscure Batman villain. Batman does not appear in the story, but his gloved hand does, snaking out from a bank of shadows, in the script’s final action line.

[14] Notable alumni: Tom Hanks, Ryan Coogler.

[15] Jim Lee, one of the artists who established Image Comics, now serves as Chief Creative Officer for DC Comics. He was born in Seoul, South Korea, and he credits sequential art—the juxtaposition of words and images—with facilitating his acquisition of a second language. Comic books helped my father improve his English, too.

[16] Rest in peace, Steve Ditko; rest in peace, Jack “King” Kirby.

[17] The DC supervillain Bizarro has terrorized Superman for more than half a century. The character is often portrayed as a failed attempt to clone the Man of Steel, and thus he is equal parts Superman and Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a cracked mirror-image of the hero he was meant to be—a Nega Superman, or Superman’s Jungian shadow. As such, his powers are equal but reversed (e.g. he has freeze vision instead of heat vision). Bizarro is lumbering, dimwitted, and decidedly inarticulate. He is portrayed most compassionately (and, perhaps, most effectively) in Matt Wagner’s underrated limited series, Trinity (2003).

[18] Literally: “overman”; colloquially: “superman.”

[19] Recounted by Michael Uslan himself in Shadows of the Bat: The Cinematic Saga of The Dark Knight Part 1 and in his memoir, The Boy Who Loved Batman.

[20] Superman has been considered the natural (i.e. most powerful) leader of the Justice League of America, DC Comics’ all-star super team, since 1960. In any case, he was a founding member in The Brave and the Bold #28.

[21] He won, of course.

[22] From his essay “Enthymemes, Examples, and Rhetorical Method.”

[23] Rest in peace, Brother Muhammad. What you did during the Vietnam War was right. What you did after the Rome Olympics—when you went home to show them your medal at that diner, and maybe buy a burger or a cup of coffee while you shook hands and smiled, only to be kicked out—was right, was powerful. You will always be a Superman to me.

[24] Marvel Entertainment Group and Marvel Comics, as they exist today—as an arm of the Walt Disney Company—is not the comic book publisher of my childhood. In 1996, a comics industry bubble burst, and Marvel’s stock value collapsed. They merged with a toy company. They sold off motion picture rights to Hollywood. They mortgaged certain characters to Merill Lynch in exchange for the funds to reacquire some of their film properties and start producing the pictures themselves. Then, in 2009, Disney acquired them—all of them—for $4.3 billion. Marvel as I knew and loved it has been dead a long time. These Disney movies are the reanimated corpses of my childhood fantasies. Dark-eyed zombies. When they are great—and, do not misunderstand, they are sometimes great—they are like the dedicated changeling my mother walked in on in her kitchen as I sketched furiously in her notebooks.

[25] Hereafter referred to as “they.” The “they” of John Carpenter’s They Live (1988). The “they” who live and sleep and act in ignorance.

[26] Any additional obstacle you can place in the path of your protagonist will only work to reveal their character dynamically by the way they choose to overcome it.

[27] I did create those ninja brothers, and I suppose they were Japanese, but to be honest, I never considered them as such. Their status as ninjas came before race, and if you had asked me then, I might have told you that their race was “ninja.” I never drew them, or even imagined them, without their faces covered by their masks. And I know why I didn’t draw many superheroes who were women. Whenever I attempted to sketch the female form, I could not, for the life of me, get their bodies right; they all looked like muscle-bound men. Once, as a child, I overheard my father’s cousin—she liked to draw and was talented—as she confessed that she struggled mightily whenever attempting to draw male bodies. I figured that was how it was for most artists and went back to drawing musclemen.

[28] Thanks to Marc Bernardin, Donald Glover, and creators Brian Michael Bendis and Sara Pichelli, there is now a version of Spider-Man (among many) named Miles Gonzalo Morales.

[29] Wonder Woman, an Amazonian princess who was molded from her island’s clay, is often depicted having blue eyes and fair skin—like Snow White.

Alexander Ramirez is an instructor of record and doctoral candidate at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Previous work has appeared in Image Journal and Black Rabbit magazine.