On July 16, 1985, an explosion occurred during the dismantling of a sewage treatment plant in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Local residents refer to this event as "Toxic Tuesday." Image: The Cedar Rapids Gazette.

Contingency Plan

By Colin Lyons

Mount Trashmore is located near the downtown of Cedar Rapids Iowa. Over the years this site has been the location of a labor community, a quarry, and a landfill, and is now in the process of being transformed into a park. Cognizant of this multifaceted history, I will initiate a site-specific installation at Mount Trashmore, titled Contingency Plan. Reflecting the life cycle of the decommissioned landfill as well as global ecological futures, this installation examines the difficult environmental realities we face, while considering the complex local histories that have contributed to our present situation.

On July 31, 2006, Mount Trashmore was closed after more than four decades of operation. Looming high above Cedar Rapids, this vast mound of trash has both troubled and intrigued city residents. They have advocated for replacing it with parkland to provide a sanctuary from the industrial activity that surrounds it along the Cedar River. The closing of Mount Trashmore, officially known as “Site One,” fit conveniently into the city’s broader redevelopment plan. This included construction projects in the Czech Village district to the west and the development of New Bohemia across the river, an area previously known as the South End, which was rebranded as part of an effort to connect the district with its historic past.

Cedar Rapids named 2008 the “Year of the River” in order to celebrate the vital connection between the city and the Cedar River that runs through its core.[1] But in 2008, the river took on a very different significance. It rose thirty-one feet, far exceeding the 500-year floodplain level as measured by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and leading to one of the worst floods in American history. Large portions of the downtown were destroyed, displacing an estimated 10,000 people. In the wake of this crisis, Mount Trashmore was reopened, and 430,000 tons of flood debris were added to the landfill, piling thirty-four feet onto the mountain of trash.[2]

In response to this catastrophe, the city elected to accelerate the timeline for New Bohemia’s revitalization plan. Replacing flooded single-family homes with revitalized housing was only one aspect of the plan, which proposed the construction of an urban market and the development of a pedestrian bridge linking the neighborhood to Mount Trashmore. Furthermore, the plan called for the demolition of the long defunct Sinclair Meatpacking Plant. This has since been accomplished, a levee and pump station replacing the industrial site as of January 2018. Mount Trashmore itself was permanently closed in 2013, and is currently in the process of being transformed into a public park and butterfly sanctuary.[3]

Not only are four decades of discarded material buried in this landfill, contained within the rubble are the traces of a fascinating and largely forgotten history of labor, migration, extraction, and waste. Located directly across the river from Mount Trashmore, the Sinclair Meatpacking Plant was the earliest industrial site established downstream from the city center. By 1878, it had expanded to become one of the largest packinghouses in the United States, spurring a massive wave of Czech migration to Cedar Rapids between the 1870s and 1920s.[4]

As a result, a shantytown, nicknamed Stumptown, rose along the southern bank of the river. Accessible only by a railway bridge and located between a river, railway, and quarry, Stumptown remained largely disconnected from the rest of Cedar Rapids throughout its nearly ninety-year history. During this time, the shantytown experienced several catastrophic floods, including disasters in 1906 and 1929 that required emergency rescue. In 1934, most of the residents were displaced to make way for a state-of-the-art sewage treatment plant. Although a significant advancement for city sanitation, this was a blow to the already marginalized community of Stumptown. Finally, after a major flood in 1961, the remainder of Stumptown was demolished to accommodate an expansion of the sewage treatment plant. Decades later, on July 16, 1985, a fire started as the facility was dismantled, spewing clouds of smoke containing hydrogen chloride and forcing the evacuation of 10,000 residents. This day became known as “Toxic Tuesday.”[5]

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the Mount Trashmore site was also home to Snouffer Quarry (later renamed the Martin-Marietta Quarry). This 140-feet deep limestone quarry, a source of concern for Stumptown residents due to debris from frequent explosions, was in continual operation for over sixty years, until it was purchased by the city for its new landfill in 1965.[6]

In the summer of 2018, I will install a site-specific installation at Mount Trashmore. Contingency Plan has been designed to integrate with the area’s proposed rehabilitation projects, and will acknowledge both the complex history of this location as well as the challenging environmental conditions we face.

In consultation with Rick Fosse and Jeff Crone from the University of Iowa Engineering Department, I am developing historic monuments which double as symbolic geoengineering prototypes. A series of glass vessels containing iron artifacts and diluted sulfuric acid will be perched atop copper-plated scaffolding that resembles a water-tower. Employing the industrial debris left over from demolition efforts at the Sinclair Meatpacking facility, this process will convert the site’s industrial waste into iron sulfate, the primary ingredient in ocean fertilization projects.

This process will simultaneously etch and restore the debris, resulting in glistening artifacts. The locations of these two monuments will encourage viewers to retrace the steps of laborers, passing by the former neighborhood of Stumptown, the ruins of the Packinghouse Bridge, and the existing traces of the Snouffer Quarry.

If the river breaches the 1000-year flood line, as measured by FEMA, the valves are to be opened to release the iron sulfate solution into the river, where it would generate the growth of phytoplankton.

Iron fertilization is one of the few geoengineering processes to move beyond the theoretical. In 2012 Planktos Inc. conducted an unsanctioned open-air experiment, dumping 100 tons of iron sulfate off the coast of British Columbia. In theory, this technique could spawn an artificial plankton bloom, which would simultaneously boost the local fishery while absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. However, concerns about this project’s effectiveness towards carbon sequestering, as well as the potential ecological ramifications remain unresolved.[7]

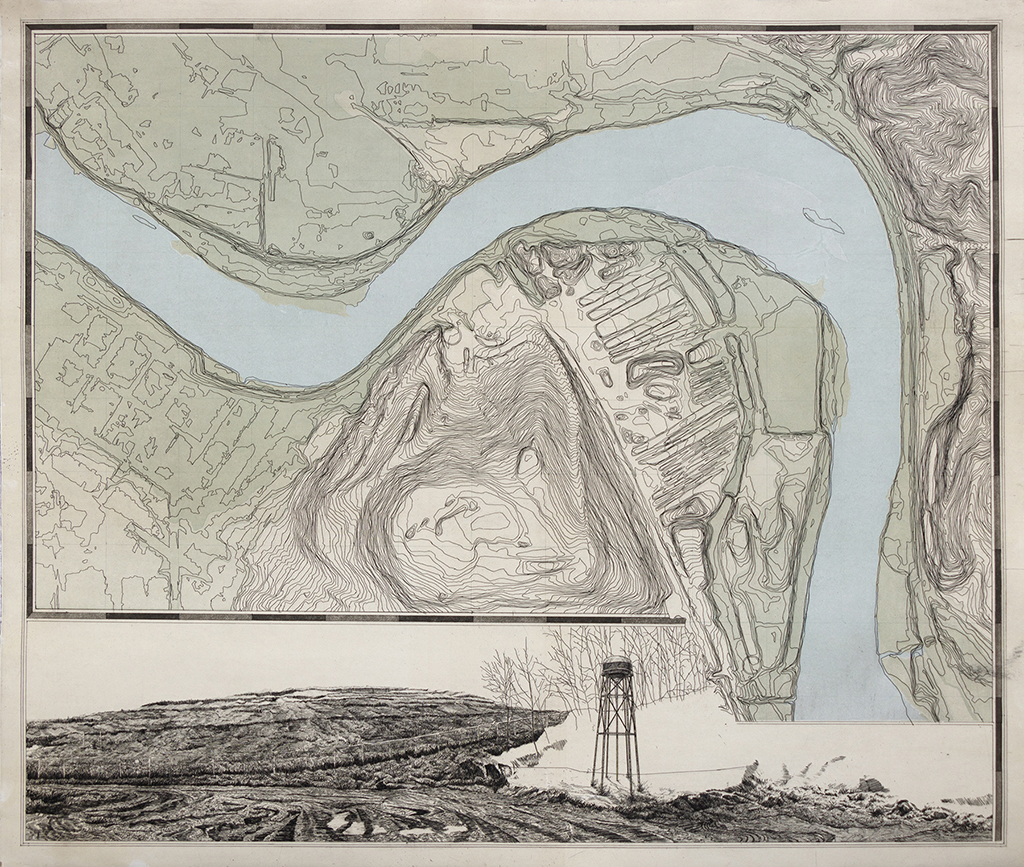

Contingency Plan (Map). Etching on paper (printed with ferric chloride and iron sulfate pigment), 24x28 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

In Cedar Rapids, Contingency Plan proposes an act of geo-engineering at such a small scale that it would be largely symbolic, leaving behind neither measurable positive or negative environmental impact. Instead of a practical geoengineering prototype, the monuments will stand more as a future-oriented satire: time capsules which project a vision of the near future based on the realities of the present.

At its core, the science of geo-engineering attempts to mimic, accelerate, or amplify natural processes of carbon reduction using highly invasive means. Geo-engineering acknowledges both the imminent ecological threat that we face and the likelihood that society will fail to make necessary adjustments in time.[8] These strategies form a dystopian contingency plan which, employed alongside mitigation efforts, strive to preserve a close approximation of our present ecosystem. But at this point, even prominent researchers in the field acknowledge the inherent risks involved in implementing large-scale, strategic chemical spills. Geoengineering is not a substitute for reducing carbon emissions, but at some point, might be a necessary measure to buy us time. The key question may be: Who has the right to experiment with the environment when the burden of responsibility and the burden of impact are asymmetrical?

Throughout the lifespan of this project, its implementation will directly reflect changes in public policy around environmental regulations, climate change, and carbon emission targets, as well as technological developments and research within the field of geoengineering. Built into the framework of the project is a closure period which reflects the life cycle of Mount Trashmore. Presently, Mount Trashmore is subject to a thirty-year closure period, during which the Solid Waste Agency must continue to monitor the site while maintaining responsibility for all post-closure costs. It also requires that any permanent construction be subject to additional permitting, as the landfill is expected to settle over the next several decades, due to decomposition of organic material. Until 2038-–when the site’s closure period expires–-the release valves of the glass vessels containing iron sulfate will be deactivated, which will allow for adaptations based on future technological research and ensure responsible handling of the project post-closure. This also enables the project to become intertwined with ongoing discussions regarding emissions targets and reduction efforts, as well as the efficacy and ethics of geoengineering technologies.

Each glass vessel will be etched with the following text:

CAUTION: CONTAINS FERRIC SULFATE

1) If through future research, iron fertilization proposals have been declared ineffective in sequestering carbon, or pose significant environmental consequences, the contents of this vessel should be neutralized, and the valve permanently sealed.

2) If through future carbon reduction efforts, global emission levels meet targets recommended in the Paris Climate Agreement and geo-engineering efforts are deemed unnecessary, the contents of this vessel should be neutralized, and the valve permanently sealed.

3) If by 2038, upon the expiration of the 30-year closure period for Mount Trashmore, carbon emission targets have not been met, and after significant scientific research, iron-fertilization geoengineering has been proven effective, the valve should be activated, and the contents released upon the event of the next 1000-year flood.

The monuments at Mount Trashmore will be beautiful and frightening, acknowledging both the promise and risk of techno-solutionism. Depending on your perspective, this project will represent a dire warning about the environmental risks involved in geo-engineering, or a sign placing hope in human ingenuity and resilience. Each time the water breaches the banks, it will leave a visible trace on the copper scaffolding, marking the water level with a green layer of oxidation. As such, these structures will at various points in their lifespan function as monuments, recording devices, and in the event of catastrophe, practical climate engineering experiments.

At this time, the more significant issue facing the Cedar and Mississippi Rivers is not, in fact, a lack of nutrients but rather an excess of phosphorus and nitrogen in the watershed, largely caused by agricultural runoff. This has led to a rise in toxic blue-green algae, a problem which iron fertilization proposals risk exacerbating. With this in mind, a second monument containing ferric chloride (also derived from dissolved artifacts), will be installed on Mount Trashmore. Recent studies suggest that this chemical may help to control the release of phosphorus, inhibiting the growth of toxic algae blooms.[9] This capsule, designed to be released shortly after the iron sulfate, will counteract its possible negative consequences. When discussing geo-engineering, we imply a synthetic re-creation of ecological balance. The presence of a second capsule designed, in part to correct the negative impact of the first, is a nod to the pendulum swings of overcompensation inherent in our collective responses to catastrophe.

Detail from Contingency Plan (prototype), 2017. Artifacts (Sinclair Meatpacking Plant), plexiglass, aluminum, glass, grow-lights, sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, copper sulphate, water samples (Cedar River), phytoplankton, ventilation unit, 58 x 95 x 22 inches.

In discussing the waste management practices of Mount Trashmore–and most other North American dump sites–Solid Waste Agency Director, Karmin McShane described this methodology as a kind of dry tomb. It is a repository for the entire material history of Cedar Rapids, carefully preserved in this hermetically sealed mound. With this context in mind, I have also proposed that a modest limestone monument be embedded into the exposed traces of Snouffer Quarry. The material for this monument will be quarried from the former site of Lithograph City, a short-lived company town which stood approximately one hundred miles up the Cedar River. Once the premier site for lithographic limestone in the United States, the town rose to prominence between 1914 and 1915, when Bavarian Limestone was a banned import during World War One.[10] Yet by the end of 1915, the shortage of American lithographic limestone had expedited the development of plate lithography making the product quarried in Lithograph City (and by extension, the community itself) obsolete. Cast around one of the industrial ruins scavenged from the Sinclair site, the interior cavity will contain and neutralize the byproducts of my chemical reactions. Limestone has long been used as the industry standard for chemical neutralization tanks. This monument would form a direct material connection to the quarry which lies beneath Mount Trashmore.

Together, these monuments attempt to reframe our thinking about post-industrial sites, shrinking the distance between ourselves and the sacrificial landscapes that we are all complicit in creating.

1 City of Cedar Rapids, Iowa Cedar River Flood Control System (FCS) Master Plan, City of Cedar Rapids, 2015, p.5

2 Rick Smith, “Capping, closing Mount Trashmore should be complete by early August”. The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, April 17, 2017.

3 Brian Morelli, “No kidding: Goats to clear vegetation at landfill in Marion”. The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, September 2, 2017.

4 Eric Barr, History of T.M. Sinclair & Company Meatpacking Plant. The Louis Berger Group, Iowa Homeland Security and Emergency Management Department: 2008, p.9

5 J.M. Flansburg, “Smoke forces mass evacuations” The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, July 16, 1985.

6 Samuel Calvin, Annual Report, 1906 with Accompanying Papers. Iowa Geological Survey: Des Moines, 1907.

7 Mark Hume. “UN questions ocean-seeding test off coast of Haida Gwaii,” The Globe and Mail, Oct. 23, 2012.

8 David Keith, “Geoengineering the Climate: History and Prospect”. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000.

9 Keith Gerein, “Adding iron to lakes infected with blue-green algae could stop blooms, University of Alberta study suggests”. The Edmonton Journal. February 26, 2016.

10 Suzanne Beisel, “The Story of Lithograph City.” The Annals of Iowa, Vol. 36, No. 6 (Fall 1962), p. 466-468.

Colin Lyons is a Canadian printmaker whose work fuses printmaking, installation, and chemical experiments. His recent projects consider preservation in an age of planned obsolescence and resource depletion, and reflect on issues around geo-engineering, urban renewal, and brownfield rehabilitation. He is an assistant professor at Binghamton University (SUNY). He would like to thank the Grant Wood Art Colony and University of Iowa Office of Outreach and Engagement for their support of Contingency Plan.