Complex List

Knowing where things are, where things go, and how it feels to know

by Cris Mazza

Photo courtesy of Cris Mazza.

After November 2016 happened to us, I wrote: Two weeks in, have we all started, and abandoned, an essay about how this feels? Then it was abandoned.

Before November 2016 happened to us, congestive heart failure completed its run, ending my mother’s sixteen months of hospice. In Spring of 2016, while the world was likewise occupied crafting digital memes for more pressing concerns, I filled hours of absorbed concentration (and a compartmentalized avoidance of grief) making a slide show of her life. It started with the earliest black-and-white snapshots, Mom as an infant, 1925 or ’26, lifted from the brittle black pages of my grandmother’s photo albums; then my mother’s own black-and-white snapshots, in an equally fragile album, high school and college years in Boston and moving west in 1946 to her first job teaching P.E. at a boarding school in Southern California. I then moved on to scan her many thousands of color slides beginning in 1950, taken before she went back to color snapshots in 1982, and to digital in 2005. Swimming, skiing, archery, field hockey, sailing, hiking, camping, lifeguarding; and after meeting my father, she embraced fishing, hunting, gardening, concocting feasts, raising children, creating parties, leading girl scouts, more camping and hiking; driving the interstates to visit zoos, theme parks, museums, monuments both natural and man-made; after retirement she visited Europe, Canada, Mexico, Alaska, Panama, taking trains and huge cruise ships plus one small tour vessel that she watched sink after evacuating to a rescue boat, bemoaning that her camera was on the floundering ship so she couldn’t take photos of it going down (she saved the news clippings instead). Her life was a month short of ninety-one years, her lifetime photo collection numbered over five thousand. The slide show was twenty-five minutes, 275 photos. It was the weeks of hours of putting it together that made it seem I could hold the whole of her life in a comprehensible and continuing entity.

Photo courtesy of Cris Mazza.

Then when November 2016 happened to us, I needed a new method to recede, to let my brain imagine living in another era and elsewhere, to muffle the fear and calm the agitation of ubiquitous news reporting. I became immersed in a genealogy project, working with some distant cousins I’d never met and whose political alliances I didn’t know and didn’t ask. Like a biologist narrowing the known world down to the illuminated circle at the end of a microscope, my deliberation was the size of my monitor’s blue-lit square. Documents from ship manifests, marriage listings, censuses—1890, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930—gave me three great-aunts all named Maria with occupations called typewriter, dressmaker, embroidery, referring to the worker and not the machines being operated. Their Italian middle-names mutated from Elizabetta to Eliza, from Grazia to Grace, from Raffaella to Anne to Mary; and their mother Fortunata was born with the same Mazza surname as her husband. Never getting off my ass, I found two Mazza heads-of-household per each street address—with wives, sisters-in-law, children, nieces, nephews — whose employment developed from grocery to metal shop to jewelry; WWI draft cards that lied about a dependent mother who had died two years prior; a sister marrying her deceased sister’s husband who was also a cousin to both; names disappearing from Brooklyn and showing up in New Jersey at another crowded multi-family house. Lives being moved, morphed, maneuvered, maintained, managed, between 1895 and 1935. Lives already lived. In reverie: re-dramatized, re-traveled, re-invented, re-invigorated … instead of doing the same to my own.

Photo courtesy of Cris Mazza.

When January 2017 started to happen to us, my canine partner in training, in dog event competitions, in life, consumed two searing weeks with a chaos of illnesses and my failed attempt to thwart a final decision. I couldn’t save him, but I saved the evidence of him: In some cases, whole folders from my file cabinet—health records, kennel club registries—moved intact into a plastic envelope and into his archive box, in other cases, separate acid-free letter-sized envelopes organized: his paper pedigree and dog-magazine articles about accomplishments amassed by the litter he was part of; score sheets from memorable wins that I no longer specifically remember; genetic clearances for his hips, heart and eyes before he began his standout career as a stud dog, and the contracts with those who bred to him; his AKC title certificates and programs from the national championship performance events he attended; his puppy collar, last adult collar, baby teeth, swatches of his longest fur, a piece of white window blind he chewed in panic when I moved and left him alone in a new house; five sympathy cards, one of them from the vet whose care was largely a long list of medications that helped kill him; and a certificate inviting him to Westminster that arrived a month after he was gone. His 11x17” box then lifted to the top shelf of the closet that already holds the blue shawl worn by my great-grandmother when she got married in the lighthouse where her father was keeper; fishing lures from the 1930s and ’40s, which my father actually used, now antiques; a hand-embroidered tablecloth made by my mother and given to her mother for Christmas almost seventy-five years ago; and many other boxes of family archives.

At some point I noticed, numbly, with little surprise or indignation, that I’d lost sensation in erogenous zones. Meanwhile, I filled a folder with loose slips of paper, each containing a scrawled memory exemplifying his personality, with intention to someday put each into a single exquisite sentence. But I never did. Instead, I lost myself in 1946, the occupation of Germany and my father’s assignment there overseeing the radio corps; the transmission of the Nuremberg trials to the U.S.; a train depot where war and manufacturing materials were being gathered and redistributed; and a group of German POWs housed in the depot whose rations were meager, who were not allowed to have radios, but who planned and invited my father to poetry readings. Through my father’s paper archives and artifacts, and out of questions he was having difficulty answering, I built a story he never told, beside an overview of American policies in the German occupation. The concerns and resulting decisions of General Eisenhower, and the never-quite-averted retaliation plan to starve Germany, both rattled and strangely assuaged my avoiding-2017 self (there were always shitheads!). But mostly the work cocooned me successfully through 2017, except that my father died three days before the final essay was ready to be published.

Photo courtesy of Cris Mazza.

Photo by Cris Mazza.

While 2018 was happening to us, almost exactly in the middle, there was a week of can’t-be-grasped-unless-you’ve-done-it, face-to-face stare-downs with existential nihilism: clearing out Mom & Dad’s residence of fifty-plus years, which made it also my childhood home. The WiFi and sole TV already disconnected, no better way to remain insulated from the looming end of democracy, apparently as hopelessly chaotic as the collapse of my beloved dog’s body. In contrast, our father passed easily with a few mumbled words, possibly to our mother, a final exhalation, a horse-drawn trip into a military cemetery, the clear cry of a bugle playing taps. The trauma and demise of his household over the week that followed: ten times the tumult. Then my little station wagon headed east, loaded with material for narratives that might never be written because, mercifully, I was also loaded, to the car’s capacity, with more material for the family archives. Besides a few hardbacks from an earlier era of book reading (with Mom’s bookplate: 1938 illustrated The Story of Mankind and 1931 Leaves of Grass; Dad’s bookplate in the 1944 boxed set of Shakespeare, even though that year he was in the Army anxious to get over to Europe before “it” ended), I packed: approximately a thousand loose snapshots stripped from forty to fifty post-slides/pre-digital photo albums (leaving five times that many still entombed in the plastic pages); my share of Mom’s watercolor paintings and her snapshot record of all her (hundreds of) paintings; a portfolio of Dad’s military papers—every single military order, some still in triplicate, requests and approvals for leave, instructions for storing and wearing officers’ uniforms, receipts for military issue, mess cards that instructed Retain This Card, so he did…for seventy years—which I’d organized but he’d never looked at the year before. All of this plus unexpected bounty: from 1946 Berlin artifacts to a never-opened tube of educational posters about nuclear fission circa 1950; from letters my parents had written to each other (Mom planning their children’s names a month after the wedding) to Dad’s college composition essays upon his return to school on the G.I. Bill, with titles like “Youth of Today” (topic was juvenile delinquency), “Can He Express Himself Freely?” (first amendment), and “The Guard” (about the unit of Polish Guard under his command in 1946 Nuremberg).

Photo by Cris Mazza.

Photo courtesy of Cris Mazza.

Photo courtesy of Cris Mazza.

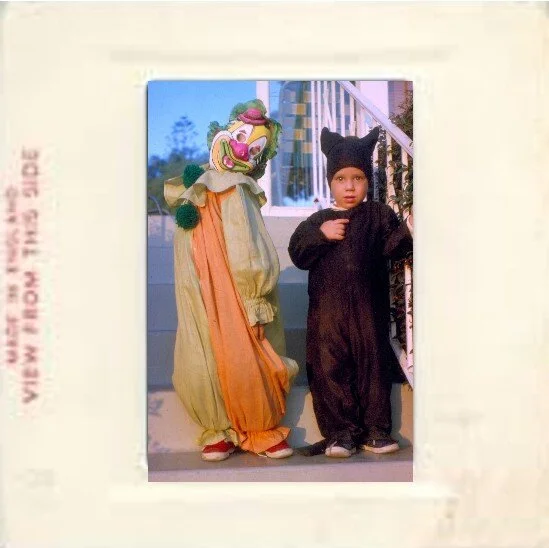

As 2018 dragged us to its last days, I finished archiving the treasures gleaned from the family compound, including scanning the thousand-plus snapshots and organizing them by date, then systematizing the snapshots of every watercolor my mother had produced (not by date but by subject matter). So, when 2019 began happening to us, I went back to her thirty-plus years of family slides, and not only began to methodically scan the rest of them, but I wanted them returned to their elemental order, by date and numerically in original film batches. Through the ’60s and ’70s, Mom had acquired dozens of Airequipt slide magazines and began making slide shows by subject instead of by each roll of film, most notably of each of her five children in childhood. Many other slide magazines did stay in date-oriented sets—excursions, vacations, holidays. Then, in the ’90s, she decided she would take apart all the old slide magazines and make slide carousels for each of her children—i.e. divide all of the thousands of slides among us, assessing for each slide which of us would value that image the most. This project was unintentionally terminated when only two carousels of eighty slides each were completed. The rest of the slides were either loose and loosely organized by our names in old cassette-tape boxes, were still in a slide magazine (almost half of them), or still in boxes from photo labs (almost another half, and not always the original box, dates and subjects crossed out and new ones written over). I liberated every slide from its magazine, carousel, or box, appropriated my dining-room table plus a few auxiliary tables, and worked for months: sorting slides by year, then sorting each year by separate dated rolls of film. All the while I was also scanning, labeling scans with the year first in the jpeg’s name, organizing the scanned jpegs into folders by “era” (where the family lived) or subject (like camp). After every slide was in order in its original film batch — raising some arresting imaginary stories of film disasters such as when a roll of film for a trip to Maine had all of four surviving slides—I inserted each into a plastic archive slide sheet, twenty slides per sheet; then twenty to twenty-two sheets in each slide-sheet binder, seven such binders in all. The first two-thirds of my parents’ life together, from 1950 through the early ’80s, stacked itself on my computer, in plastic pages, and in my imagination: their wedding and honeymoon, their early residences and omnipresent gardens, their budding family—first and second babies warrant many dozens of photos at two months then again at three, four, five months; rolling over, sitting up, sucking on toys and fruit and drumsticks, dressed in starched ruffles and bonnets or denim overalls or not dressed at all. Then as more children came along, events start to amass: our birthday parties and Halloween costumes, our Easter finery and Christmas bikes, our first (and many after) hooked trout, our first (and many after) hikes in the Sierras; best friends, cousins, grandparents, family dogs, pet roosters and butterflies, litters of white bunnies soon to be dinner but for now bouncing on the lawn; snowball fights, sandcastles, riding the surf on canvas rafts, running naked in sprinklers; The San Diego Zoo starting in 1953, Knott’s Berry Farm starting in 1955, Disneyland starting in 1958, and the now defunct Santa’s Village also in 1958; finger-painting, science fair projects, musical instruments, scout uniforms, batting stances, patio cookouts; countless harvests of voluminous fruits, vegetables, flowers and eggs; equally innumerable hunting yields of duck, dove, quail, geese, and rabbit; girl and boy scout campouts, Christmas festivities, marching band, first cars and first formals, graduations; driving trips across the country, I-40 attractions and East Coast beaches, Washington, D.C., Boston, Maine, Niagara Falls, Yellowstone. And threaded between every event or milestone or accomplishment or scenic excursion, the continued evolution of their last house, our family compound; built on the side of a hill and, over the course of fifty years, terraced with handmade walls of rock dug out of the same ground by one man, assisted by his wife and children.

Photo by Cris Mazza.

Photo by Cris Mazza.

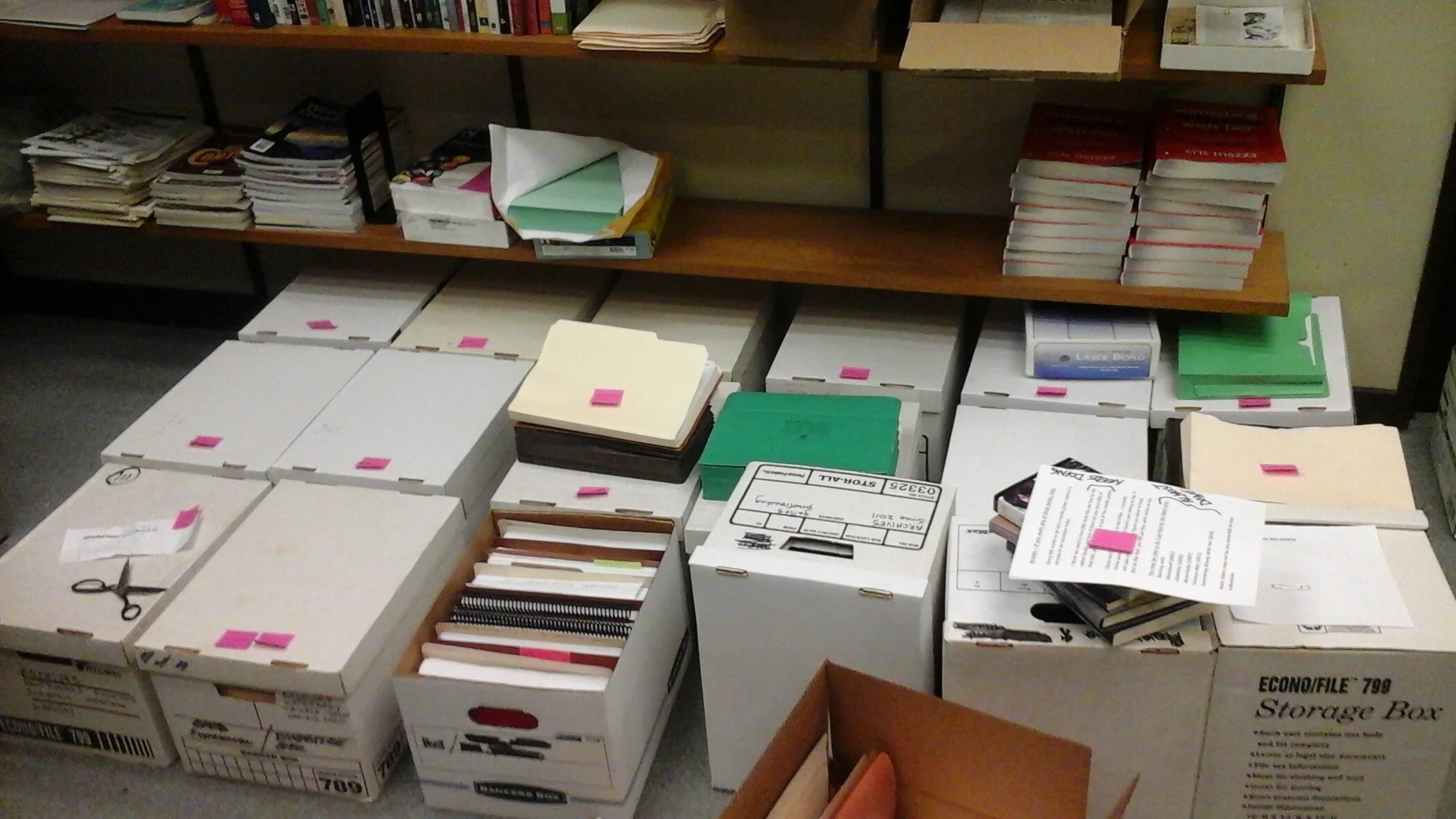

While 2019 was happening to us, to some more than others, I was given the use of a research assistant—a PhD student exiled from teaching by threats of fabricated publicity from a spiteful undergraduate. Together, on the floor of my campus office, my RA and I amassed and began to organize the boxes of archived papers that had been collecting for over four decades—going back to high school material. Not only the manuscripts—many versions of each novel and short story in hard copy from the first two-thirds of my career, pre-digital through semi-digital when submissions still had to be hard copy—but also the submission records for each on both 3x5 cards and an overall handwritten log; published versions of stories, essays and excerpts in literary magazines and anthologies, roughly two hundred fifty, sliced out with an X-Acto knife by my research assistant; letters from publishers, agents and editors, including acceptance letters and contracts for the aforementioned lit mags and anthologies. Then alone, in my 2019 summer job, I went through four document boxes containing every review and piece of publicity for each title; every other random piece of correspondence, from a N.Y. editor who unofficially agented and advised for a decade and then withdrew when I went through an agitated period, to a few enigmatic cards and a letter from David Foster Wallace; and every flier or poster from many (not all) of the events I was invited to. At home during July days in the upper nineties with similar numbers for humidity, I stood on a concrete floor in a cooler, moderately drier basement, sorting media materials by book, sheathing fragile newspaper clippings in plastic sleeves, and occasionally stopping to read about an author who was “a subversive, anarchistic writer…hardly forgettable,” who wrote fictions “remarkable for the force and freedom of their imaginative style” and from whom “talent jumps off like an overcharge of electricity,” but who had—as publicity became author-generated, reviews went digital and review venues extinct— grown more and more invisible, and, apparently, forgettable.

For four years, as 2020 now approaches, the lives of my ancestors and my parents; the memories of my dog and my own childhood; and the (d)evolution of my writing career have all paraded before my perception (aka passed before my eyes). Not just watched aghast, but re-lived, re-invented, or psychologically analyzed with questions and guesses: Is it significant that my dad preferred Patton over Eisenhower, and before he died was enthralled with the current source of my need-for-distraction, #45? What did my mom mean when she wrote to my father, early in their marriage, “we probably won’t have as many girls”? And could she hear the subtext when she wrote, “I don’t care for Jr. but if you like it I do too.” Does this explain how she moved from Leaves of Grass to Danielle Steel? What were dad’s real tacit feelings when his third child was yet another girl, despite my mom’s assurance? What was my role in my dog’s suffering, and did his crisis impact my ability to feel? How wrought was I when the N.Y. editor asked my agent if I was dangerous and decided to cut off contact?

Archiving, and the resultant engrossing time warp, did build and (barely) maintain a sandbag breakwater to keep 2016-2020 from flooding in. It also provided a means to gape at the world my grandparents chose to enter, adopt, to sign allegiance to, raise a family in; the one my parents met head-on, embraced, settled into, accepted without question was right (in several meanings of the word); the world I was handed after a baby boom childhood, where debt-free higher education could be had in exchange for putting on a band uniform and blowing through a trombone; and the literary world I was initially welcomed into, where it seems I thrived in a sub-category, until—like my ancestors and their life endeavors that could only be fantasized; and my parents’ lifetime of exploits, landscaping projects, paintings, and preservation of it all in photographs; and now my own boxed career prolonging the list—time, talent, and tenacity ran their course.Here’s my essay about “how this feels.”

It feels like dying.

Cris Mazza’s new novel, Yet to Come, will be from BlazeVox Books. Mazza has eighteen other titles of fiction and literary nonfiction including Charlatan: New and Selected Stories, chronicling twenty years of short-fiction publications; Something Wrong With Her, a real-time memoir; her first novel How to Leave a Country, which won the PEN/Nelson Algren Award for book-length fiction; and the critically acclaimed Is It Sexual Harassment Yet?